Have you heard of Lost Glove Syndrome? I hadn’t either until I thought for a long time about my life, why I travel the way I do, and made up a philosophy for it.

Everyone knows what I’m talking about when it comes to a missing glove (just substitute “sock” if “glove” doesn’t work for you). Whether they shield you from frigid weather, or add retro personality to an outfit, when one glove is missing you’re incomplete.

Having one remaining glove isn’t bad, but it’s not great either. As you search for the missing glove you have time to think…about what it means to you and why you want it so badly. So when you do finally find it you understand something profound: you have so much more than two gloves. You have a matched pair.

As applied to life, the quest epitomized by Lost Glove Syndrome is why I’ve been willing to humble myself during the journeys that follow.

Like that perfect pair of gloves, I suspect there are elements of me out there, somewhere, which, when encountered, will make me better, in a so-much-more-than-whole way.

It’s why, for me, travel isn’t a quest to see. It’s a quest to be.

Because I have Lost Glove Syndrome in a serious way, travel has become more than just passing time on an activity. It’s a process by turns uncertain, monotone, exhausting and sometimes embarrassing, spiked by revelations and encounters so intense they’re like a miracle.

People talk about travel taking me out of my comfort zone. That’s never been my goal.

Why would I put myself into discomfort for days on end just to say I was uncomfortable? Besides, eventually the outside of that zone becomes comfortable enough that the whole term loses its meaning. And then what?

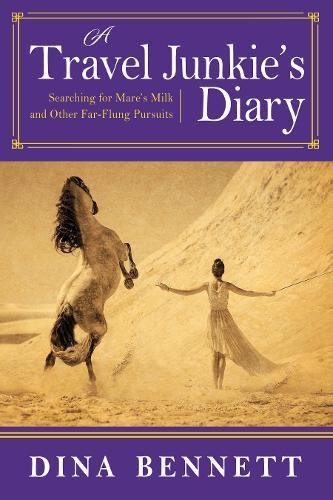

Photo by Craig Philbrick on Unsplash

No, the reason I repeatedly am willing to open the door to a car and set off on the sort of road trips that populate this book, is my search for the proverbial missing glove, that element of my character I know is there and without which I feel unfinished. When I travel to likely places in likely ways, I find only a mirror cheerfully reflecting everything I enjoy about myself. It’s easy, comfortable—and I’m happy. When I’m in less likely places, though still on a normal trip, that mirror may show me an unflattering reflection of myself, but in ways familiar enough that I can remain unchanged.

It’s only the radically different methods and environments of these road trips that challenge me to search for an aspect of me which, if I can find it, try it on, wear it for a bit, will enhance me with that laughing “ah-ha” moment of discovery melded with recognition.

The trip that started it all was the 7,800-mile Peking to Paris car rally (which I now call the P2P) I did with my husband Bernard in 2007. Before that year, all I knew about cars as a mode of travel was to stay out of them, because I get carsick.

Following that trip, I still knew that cars and I didn’t get along particularly well. But I also knew that a specific magic took place when Bernard and I set out on the road together, passports stamped with illegible visas, closed in a car for weeks at a time, seeking the rutted tracks and backcountry hamlets where outsiders rarely go.

The tales in this book are gleaned from ten years of extraordinary and difficult road trips in the world’s out-of-the-way places, trips we embarked on after that shattering 35 days of the P2P race. The near-calamity of the P2P yielded something surprising: that when concentrating I no longer got queasy.., and something very personal as well: that by putting myself through the fire I could come out the other side a little different. And I wanted more.

I confess that, despite the passage of time, a road trip still is a mode of travel for which I remain generally unsuited.

I’m like a rat ejected from a grain bin, ripped from the comfortable predictability I crave. In the early days, I clung to the lip of that bin, longing to stay home, mightily resisting the next road trip. Now, while I don’t exactly leap from the edge of that bin, I’m genuinely happy to get on the road, even relishing that vague dread about what comes next.

I try in these stories to reveal what happens when you travel not in search of statistics and data, but for whatever happens right around you. You’ll see what I see, and I don’t hide how, like any friend, I struggle. Sometimes there’s an obvious point, but sometimes you’ll find yourself getting it, just like I did, because of the truth of the moment.

The stories themselves are organized by subject rather than date. I made this organizational leap of faith without knowing that Mark Twain had already come up with the idea. “Ideally a book would have no order to it,” he said, “and the reader would have to discover his own.” I don’t mean to be obscure in presenting things in this unstructured fashion. It just strikes me as an honest reflection of how discovery happens when traveling and how friendships develop between people who at the start know little about each other.

The travel dream we all have is for something elemental to materialize when we’re away from home, something that connects us indelibly to the life around us. Obviously, each story you’re about to read took place at a particular time, but more importantly they all are timeless in their human connection. The bewitchment of these tales is that they permit you to suspend the judgment promoted by our time-sensitive society, in which how fast you get things done is better rewarded than the quality of result. I hope that you, too, in dispensing with when and in focusing on why and who and how, will find yourself with a fresh perspective.

Mary Oliver, our great American poet, wrote an essay that starts like this: “In the beginning I was so young and such a stranger to myself I hardly existed. I had to go out into the world and see it and hear it and react to it, before I knew at all who I was, what I was, what I wanted to be.”

This applies to us all, regardless of age, experience, or opportunity.

Through my travels, I’ve learned to find opportunity for connection where others see only strangeness, to feel myself lucky where others see missteps, to know that the grass is greener right where I’m standing, to come back a different me from when I left.

I invite you to go for a walk, a ride, a journey without a map. To become, as I have, a travel junkie.