Sunset over the Nullarbor, Western Australia

![]()

The car was loaded with five backpacks and enough camping gear to set up a small refugee camp. With the added weight of five sweaty travellers the car creaked, grumbling louder with every passing kilometre. We’d hardly reached the outskirts of Perth when it finally gave up and over-heated, leaving us stranded at the side of the road wondering whether our plan to cross the Nullarbor was such a good idea after all.

Stretching along the bottom of the country, the Nullarbor Plain is one of Australia’s great road journeys. Starting at the town of Norseman, the Eyre Highway crosses 1181 kilometres of desolate limestone plateau, before finally reaching Ceduna, South Australia. In between is a whole lot of nothing – truck stops every 200km’s and not much else. A beautiful example of Australian outback, but not the sort of place you want to break down.

Putting such thoughts to the back of my mind we fixed the car and pushed on, finally reaching Norseman a couple of days later via the scenic route, travelling south through Margaret River, Albany and Esperance, eventually joining the Eyre Highway with what seemed like the entire Norseman Highway Patrol – three police cars travelling in convoy. David, one of our passengers, suddenly became very nervous. It wasn’t until later we found out why.

Nullarbor is a Latin term that roughly translated means ‘no tree’, so it was surprising to find a corridor of gum trees lining the road like obedient soldiers. The police cars eventually disappeared along with the radio signal, leaving us alone on the road with a limited supply of cassettes. The Chili Peppers sang ‘Road Trippin’ for the fourth time in as many hours and the trees gradually receded, allowing the Nullarbor to spread out ahead in glorious technicolor.

Built secretly in 1941 as a Second World War supply route, the Eyre Highway was the first road to connect both sides of Australia. Before the highway was sealed, in 1976, the crossing was a treacherous one. A friend in Margaret River, an ex-biker turned Baptist priest, remembers driving across on his Harley dodging potholes the size of oil drums. Another friend recalled making the journey with his parents in the 50’s, when the highway was just a dirt road without roadhouses. His father paid for petrol in Fremantle before being told the secret location of pumping stations along the way. Back then it took four weeks to reach Adelaide, we were hoping to do the same journey inside of three days.

Dust devils twirled across the road as the Falcon eased into the Balladonia Roadhouse. Panting dogs littered the forecourt as the temperature climbed into the high 90’s. We cooled down under some shade, gulping cold water and watching crows jump over the car, pecking dead insects off the windscreen.

WA-SA state border

![]()

Back on the road a large black & white sign announced: ‘Australia’s longest stretch of straight road – 146 km’s until the next bend’. Talking Head’s ‘Road to Nowhere’ played over in my mind as the never-ending tarmac rolled around like a running machine. Occasionally we’d drive over large white numbers painted in the road – runway markers for the flying doctors. Further down the highway another sign informed us we were about to pass through a time zone. Coming from Europe, I usually associate time zones with a new country and an alien language, out here it means nothing. Everything remains the same – same road, same dust, same heat – the only thing that changes are the hands on the clock.

The Cocklebiddy Motel rose from the desert like a petrol pump oasis, a ramshackle collection of corrugated iron buildings bathed in the tangerine light of the setting sun. We bought beer from the bar and admired the pictures of Australian sheep dogs and monster trucks that covered the walls. Our tents sat outside, pitched in the overgrown car park that the barman assured us was a campsite. Campervans and roadtrains hissed to a halt as David unrolled his sleeping bag and revealed the reason for his earlier display of nervousness. A large bag of grass tumbled from within, falling to the ground with a satisfying “plop”.

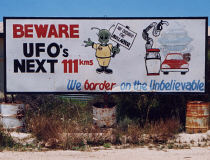

As darkness descended, the skies above the Nullarbor came alive. With no towns around light pollution is non-existent, making it the perfect place to observe stars and watch comets steak the sky. Insects whistled a constant chorus as approaching road trains hovered on the horizon, their lights warping the sky like UFO’s. Our giggles carried across the desert as we lay on our backs exhaling blue smoke, uttering an occasional “wow”. If this trip had taught us anything it was that the outback is no place to get the munchies.

The following morning brought an unwelcome surprise. Since buying the car in Darwin I’d driven over 4000 kilometres through large cities and rural towns without ever being stopped by a cop. So, I was a little surprised to come across one standing in the middle of Australia’s remotest road an hour out of Cocklebiddy. What he was doing there – 30 kilometres from the nearest truck stop and over 450 kilometres from an actual town – was anyone’s guess. I didn’t bother to ask as it quickly became apparent that it was his job to ask the questions.

“Where you heading?” He demanded, which wasn’t the most intelligent of questions, considering this was the only road and it went either East or West. “Passport and driving licence,” he continued, before I could answer. David sat in the back looking guilty as I handed over my documents for inspection. Anyone who has ever talked to a traffic cop knows there’s no point being friendly. As Hunter S Thompson once put it, “it arouses contempt in the cop heart,” so I tried my best to act non-plussed. My composure lasted all of ten seconds, the time it took the cop to request a luggage search.

We clambered out the car looking guilty and slowly unloaded the bags onto the hot tarmac. One by one the cop opened them, rooting through the layers of stinking t-shirts and unwashed underwear. He finally reached David’s backpack, pulling open pockets and prodding the insides with his car keys. David shifted nervously from foot to foot as the rest of us held our breath.

“Have a good day,” hissed the cop as he waved us on. David lit a cigarette with shaking hands as the rest of us smiled dumbly at each other. To our amazement he’d found nothing, not giving David’s lumpy sleeping bag a second glance. I put my foot on the accelerator and watched the waving policeman grow smaller in the mirror. The relieved silence that filled the car lasted all the way to the Bunda Cliffs.

Bunda Cliffs, South Australia

![]()

When explorer John Forrest came across the Bunda Cliffs in 1870 he wrote, “We all ran back, quite terror stricken by the terrible view.” In 132 years not much has changed. The cliffs are still an awesome sight. 65 metres straight down to the turquoise waters below, crashing into rocks with white water force. In the winter months, Southern Right Whales can be seen breeding in the Great Australian Bight, but today sea lions dominated the water, bodysurfing in the approaching waves. We stopped for lunch, a delightful combination of processed cheese and cold baked beans, before rejoining the road to Nundroo.

Waiting for us back on the highway was our second surprise of the day. A 50-metre road train came barrelling towards us, prompting me to slow the car to a crawl as it passed. A road train encounter comes in two waves, the first when the truck initially passes, quickly followed by a vicious blast of wind turbulence. It was the latter that caused the damage, pounding the Falcon with enough force to snap the bungee cord on the roof rack and lift our rucksacks into the air. The bags decorated the highway like victims of an RTA, sun cream replacing blood as it oozed in rivers, slowly seeping into bitumen cracks.

Reaching Nundroo we sought solace in beer, drowning our sorrows and fighting off biting ants that surrounded the tents like warring Indians. We quickly surrendered and hid inside our private domes as daylight receded.

Bunda Cliffs

![]()

We left Nundroo as the sun was rising, cruising along the highway under the watchful gaze of bush kangaroos. The final 150 kilometres fell by. Crows danced over dead wombats and small signs of civilisation appeared. The barren earth became cultivated fields. Grain silos and windmills dotted the highway and tall trees fought for space amongst a plethora of signs advertising hotels, radio stations and oyster tours. ‘Welcome to Ceduna,’ the last one read, ‘Population: 2600’.

The Nullarbor was behind us. The next challenge was to get to Adelaide, a further 749 kilometres along the Eyre Highway, but that journey could wait. Ceduna is an Aboriginal word meaning “to sit down and rest”. We took their advice and stopped for breakfast.

Questions?

If you want more information about this area you can email the author or check out our Australia Insiders page.

![]()