Cultures amuse me. They run like railway tracks – parallel, but never meeting, never quite the same – and that is where the beauty of cultures lies. Be it intra-nation, in a country as diverse as ours (India) – where, in one part of the country, women are obligated to touch the feet of the elderly, while in another, getting your feet touched by a female is a sin; or inter-nation, such as the cultural contrast between the Chinese and the English – “who believe it’s a slur on your hosts’ food if you don’t clear your plate whereas the Chinese feel you’re questioning their generosity” as quoted by an HSBC cultural advertisement uploaded on YouTube, each culture is uniquely fascinating in comparison and in contrast to another.

This is a major reason why I was thrilled when my parents announced a seven-day trip to Japan.

Coming from a country like India, known for the plethora of religions that coexist and the languages that abound, and going to a destination often referred to as “a country of cultures and customs,” I knew I was in for a cultural treat. From the moment I boarded JAL (Japan Airlines), the almost ninety-degree bows and the soft nods of the Japanese aircrew began to foreshadow how the two countries are complex cultural conglomerates which share various cultural differences and similarities, all at the same time.

Apart from simply observing the high-rises and the women garbed in kimonos, in my quest to deeply understand the Japanese culture I also interviewed around 10 Japanese individuals belonging to different gender, age, and socio-economic backgrounds. Some of these interviewees were my own Japanese friends, while others were complete strangers.

Japan & India – a Cultural Comparison

Food

My research revealed that in Japan, Western impact has clearly penetrated into the younger generation with a noticeable rise in the number of McDonald’s joints opening in the city, akin to the metropolitan cities of India. However, instead of the strong Japanese gastronomical walls coming down, it was found that Japanese food is still preferred by the youngsters who live with their families, and more so, by the older generation. One of the sixteen-year-old interviewees, Hotaka, who is an avid traveler, exclaimed “I probably eat Japanese six days a week!” which may resonate with how even today, most Indian families, regardless of the difference in their socio-economic backgrounds, come home to a meal that is predominantly Indian.

However, a noticeable pattern exists in the young work-driven individuals who prefer take-out over a home cooked meal, for the sheer sake of convenience – which could be a possible reason for the marginalization of Indian food – a major issue covered by the Times of India in the article “Recreating lost cuisines of India.” While Indian gastronomical dilution may be a hot issue right now (pun intended), the continued prevalence of traditional Japanese food could possibly be due to the presence of budget-friendly fast food chains such as Matsuya or Yoshinoya that serve traditional Japanese cuisine, described by multiple tourists and locals alike as “Delicious, fast and cheap!”

In contrast to the relatively homogeneous Japanese cuisine, India offers a variety of cross-cultural food options that correspond to its many regions and traditions.

Therefore, although Indian fast food chains exist which supply regional cuisines such as Pind Baluchi for authentic Punjabi butter chicken, or Sagar Ratna for delectable South Indian Dosas, sadly, several lesser-known regions of the country do not find adequate representation in these “popular” food joints.

Affordability is another key factor in both cultures that plays a crucial role in native food preservation – authentic Indian or Japanese food offered by highly rated restaurants tends to be extremely expensive in comparison to the same food that is being cooked in households. According to interviewee Rino Hamanishi, the difference between the “authentic” sushi, and the “regular” sushi could be a whopping ratio of $20 to $2.

Photo by Should Wang on Unsplash

Photo by Should Wang on Unsplash

Another interesting factor that surfaced was the marked tendency amongst youngsters to exotify their dietary preferences in both cultures.

“Many of my friends here (in Japan) say that they like Mexican or Italian, but they eat Japanese food most often!” quipped another interviewee. A parallel situation in India is often observed in cities like Gurgaon, where a fourteen or fifteen-year-old would possibly identify a non-native cuisine as their go-to option, but one would find the typical chicken tikka or kadhai paneer cooking at their home.

Clothing

Sadly, my short trip coupled with several interviews taught me, in the words of one of the interviewees, “Kimonos are not as common as you think!”

While I did spot a couple of women wearing Yukatas (light cotton kimono) at Asakusa and Tokyo Disneyland, similar patterns were seen between both countries in terms of how frequently traditional clothing is preferred over the classic jeans-t-shirt combo. In both countries, traditional clothing has been relegated to the margins of celebratory occasions such as Matsuri or Seijinshiki in Japan, and Diwali or Holi in India.

Based on my analysis, this is due to two key factors – convenience and expense. Authentic traditional clothing is much more expensive than Western clothes that come fresh out of conveyor belt mechanisms. According to The New York Times, an average Kimono costs $800 while a Kanchipuram sari may cost anywhere in between $95 to $1,450 – which relatively speaking, are exorbitant prices for a clothing item that may only peek out of the wardrobe once a year!

Sarees and Kimonos are both difficult to wear and manage. I had the opportunity to wear a kimono for the typical-tourist-in-traditional-attire picture. It took two people to help me wear the garment and almost 20-40 minutes, exclusive of make-up – which is not the kind of time women and/or men generally have today.

Preserving Cultural Heritage

However, these 20-40 minutes are hardly tiresome if we consider the existence of various Japanese cultural patrons who spend years at specialized schools devoted to the art of wearing a Kimono, among other traditional activities such as the Tea Ceremony – with no limits to how many years it may take to master the skill to perfection. An example of one such school is the Iida Kimono institute, mentioned by a cultural guide I interviewed in Tokyo. It boasts of “teaching the culture, traditions, and joys of Kimono.” Yurako-sensei, the head of the institution, has been teaching Japanese women how to wear kimonos for over 40 years at her school in Zushi.

Specialized institutions are not the only factor responsible for preserving the strong cultural heritage of Japan as we know it. Japanese celebrations which foster traditional attire such as Shichi-Go-San (celebrating the growth and well-being of three, five and seven-year-old children) and Tanabata (celebrating the meeting of the deities Orihime and Hikoboshi) are prevalent even today. But in that respect, Indian festivals such as Bihu, Durga Puja Diwali, Pongal and Ganesh Chathurthi also emphasize the need to wear traditional clothing specific to festivities.

Traditional clothing varies by geographical region in India, but not in Japan.

Unlike India, Japan is a country with a relatively consistent culture, being geographically not as diverse. Japanese traditional clothing is mostly limited to Kimonos, Haori, Hakama or Happi coats. The attires differ according to festivals, and not according to geographic areas.

Photo by Hassan Wasim on Unsplash

Photo by Hassan Wasim on Unsplash

On the contrary, festivals in India associated to specific areas (such as Bihu from Assam) require women to wear a Mekhela Sador (a two-piece garment that is wrapped, similar to a sari) whereas, Durga Puja from Bengal sees married women dressed traditionally in white saris with red borders to celebrate the Visarjan ceremony (the concluding day of the festival).

Every Indian wedding differs, varying region-to-region, and consequently depending upon culture and religion. A Hindu wedding requires a bride to have the 16-piece traditional set called Solah Shringar, while a Bengali wedding would see the bride in a typical Bengali saree, decorated with heavy gold or silver zari work and embroidery and often weighing up to two kilograms. While one may wonder at the immensity of the burden, the jewelry – instead of weighing the bride down – simply adds weight to her existing charms.

On a more serious note, a key similarity between both countries can be seen in the approaches that people of different ages have towards traditional clothing.

A fifty-year-old Japanese guide, with some regret in her eyes, explained, “I have learned how to wear a Kimono and the tea ceremony for years, but my daughter… she can’t. She can’t wear it.”

The same is prevalent in India as well, with youth increasingly opting for cheap and fast globalized fashion over the comfort of hand-woven Kurtis from local weavers.

Educational institutes from both countries are working to bridge the ever-widening gap between tradition and convenience.

Educational institutes and their role in preserving cultural heritage. While this may seem surreal to a majority of students studying in the more “up-scale” schools in cities like Mumbai or Delhi NCR, several interviewees from Japan highlighted the importance of educational institutes in promoting their outlook towards culture and traditions through clubs, history lessons, and field trips.

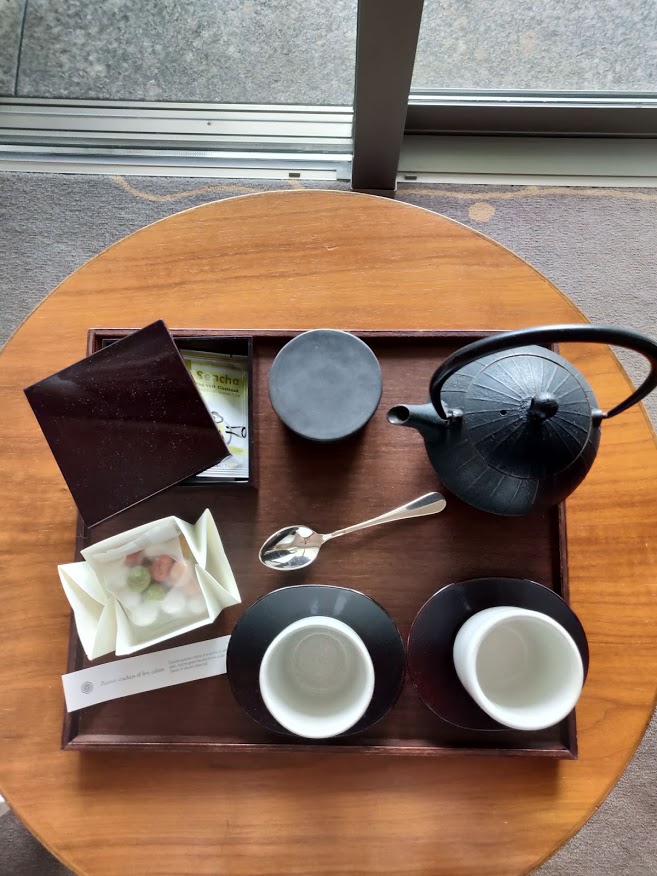

Japanese schools allow their students to be members of different clubs that nurture the growth of traditional Japanese activities such as Ikebana (the Japanese art of flower arrangement), the art of wearing a Kimono, and Japanese Tea ceremonies. An interviewee revealed that at his school, “every club takes a lot of time” with some activities consuming up to two hours, for as many as five days a week. This amount of dedication clearly shows the level of importance that the Japanese education system places upon preserving their culture.

The Japanese government mandates Primary Schools to provide basic Japanese cultural history textbooks to their students. Most interviewees also explained that Origami is a very common skill in Japan possibly because Primary Schools inculcate regular Origami lessons as part of the course curriculum (and here I am struggling to make a simple boat!).

Indian schools, on the other hand, do not focus on Indian history until the students reach higher standards in the education system.

This may possibly explain the Hindi phrase “History, geography badi bewafaa, shaam ko parho subh ko safa,” meaning, “History and geography are very unfaithful: study them at night, you’ll have forgotten everything by morning” – hinting at the subtle dislike towards Indian History as a subject that is generations old.

However, exceptions exist, and one may see equal importance allotted to culture in some Indian schools and colleges, even today. Clubs or houses in certain Indian schools and colleges are named after Indian revolutionaries, popular leaders, rivers and so on. The activities undertaken by these clubs often include few Traditional Indian activities such as Yoga, Classical Dance, Classical Music, and Rangoli making competitions, in addition to certain elite schools offering more globalized activities such as Horse Riding, Golf, and language lessons in French, Spanish, and German.

Traditional Garb in School

A point of conflict where Japanese schools seem to fall short based on my research was that although several Japanese schools do offer lessons on how to wear a Kimono, most schools do not give students the opportunity to wear traditional clothes.

Several Indian schools such as The Heritage School and The Modern School either have days reserved for Ethnic wear, or have traditional uniforms such as Salwaar Kameez. Certain Indian universities like the Christ University or Guwahati University mandate either Ethnic wear as part of their uniform or have uniforms which are traditional – allowing students to comprehend how it is critical for teenagers to have respect for the civilization that has cultivated them for millennia and recognize that they are a product of this civilization.

Japanese schools also facilitate cultural preservation through frequent field trips. According to the interviewees, regular field trips are organized where the students are taken to Kabuki (Japanese opera), Sumo-wrestling and other heritage monuments. Although Indian schools also offer trips to cultural heritage monuments, namely The Taj Mahal, The Qutub Minar, and so on, the difference, I believe is how the two cultures take into consideration the interest of the students and the extent to which they are involved. For instance, a field trip to an Indian clothing factory would not cultivate the same amount of interest in the students as a trip to a traditional Japanese weaver’s home.

I believe some things speak for themselves – like the political history of Japan.

Since Japan was never colonized and immigrants were not allowed to take up residence until 1868, people seldom speak English there. This has undoubtedly helped in cultural preservation, as in many ways the country has remained linguistically isolated. In contrast, India does not present one with this problem, being the second largest English speaking country in the world. Sahit Aula from Forbes very beautifully writes, “a person’s socioeconomic status in Indian society is approximately in line with his or her fluency in the (English) language.”

Accordingly, most Indian schools offer education primarily in English. I mention this because my seven-day-trip taught me how learning Angrezi is not the end of the world – and mastering it during the primary years in school should definitely not be one’s top agenda. I can flaunt these wise words of wisdom since I had an interaction (mostly sign-language) with my Japanese friend – Manami’s eleven-year-old brother. As he and my just-turned ten-year-old brother stood side by side, one had no knowledge of the English language beyond Yes and No; while the other, my own brother – was expected to understand extremely complex words and grammatical syntactic nuances in English, simply because of societal norms where Indians expect other Indians to be fluent in the language of the colonizers.

To conclude, I would like to draw one last poignant comparison between the two countries, because what are endings if not bittersweet?

Even as we try to sink our roots into the rich dark soil of our cultures, it crumbles beneath our feet like loose sand. In the cut throat competition of Darwin’s metropolitan desert, our cultures are falling apart.

Ninjas and samurai have become relegated to children’s cartoons, people barely wear the cumbersome kimonos or mekhela sadors any longer and the dhoti is almost a thing of the past. But sixteen years of living in the country of Bollywood has inculcated a hopeless sense of hope in me.

Through the eyes of my younger brother and the younger generation in general, I see communities, governments, educational institutions as well as individuals all working together to become increasingly aware of cultural heritage, both Japanese and Indian. This wild hope is substantiated by the fact that the more estranged we become, as the world loses itself in a perpetual identity crisis, the more we learn to amalgamate tradition and progress, culture and growth. After a hard day’s work, all anyone really wants isn’t a bed full of money, but a family to come home to and a niche to fit into.