As industry changes, ginormous structures often get left behind. Rather than let them fall into decay, some forward-thinking cities have repurposed the buildings. Below are the seven most fascinating former factories–turned–must-see museums around the world. Once upon a time, these places created commodities like boxes, mattresses, and electricity. Now they’re making inspiration, imagination, and thought.

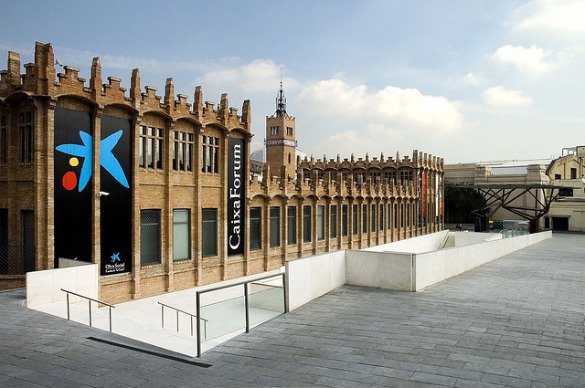

CaixaForum Barcelona

Completed in 1911 by Josep Puig i Cadafalch, an architect famous for his Art Nouveau style, this Barcelona edifice attempted to elevate mass production through humane and aesthetically interesting conditions. The castle-like Casaramona textile factory relied on natural light and electricity, instead of chimneys. Alas, it closed after just seven years and fell into such decrepitude that it eventually served as garages and stables for the National Police Force.

Today, the arresting glass-and-steel entrance by Arata Isozaki counterbalances the original brick façade and signals the shift from factory to gallery. Thanks to the charitable arm of Catalonia’s largest bank, since 2002 CaixaForum has showcased contemporary art—and charged no admission fee. The permanent collection emphasizes minimalism, including “Behind the bone is counted – Pain space” (1983), by Joseph Beuys. In this room, sure to appeal to fans of the Saw movies, lead covers the walls, creating a dark, scary place full of echoes and what look like scratch marks. More pleasurable is the view from the roof, where you can take in the hills of Montjuïc, the Palau Nacional, and the chintzy but charming Magic Fountain.

Centrale Montemartini

Down the street from Testaccio’s 150-foot–hill made from pottery shards is Rome’s most enthralling museum. At Centrale Montemartini, ancient Roman statuary, much of it representing former deities and rulers like Cleopatra, shares space with machines left over from the building’s previous life as a twentieth-century power plant, the city’s first. This juxtaposition of art and industry forms a commentary on kinds of faith: one gives objects carved from marble the power to grant wishes and influence events, while the other believes that flipping a switch will unfailingly illuminate and improve our world.

It’s also pretty cool. The museum was inadvertently created when curators needed to store works during the 1997 renovation of the Capitoline Museums. Hundreds of figures and heads were craftily arranged such that a slope of a shoulder or breast emphasizes a swerve of a dial, while the cracked steel of a decommissioned engine echoes the similarly rough history of a now headless torso. They liked the effect, and so did visitors. Despite the seeming fragility of the pieces on display, every single thing was constructed for maximum effect and longevity by craftspeople using the main materials, whether marble or metal, of their time.

Dia:Beacon

Located in a quiet hamlet in upstate New York, this museum showcases international artists, with a focus on Conceptual and Minimalist Art by Americans from the 1960s to the present. Its art and architecture have a symbiotic relationship: at close to 300,000 square feet, the structure could practically only be used to house paintings and sculpture from this period, which tend to be a little on the large side. Built in 1929, it functioned mostly as a printing factory, making boxes for Nabisco (the National Biscuit Company), until 1999. Heavy, scarred beams testify to its original use; huge windows and an open floor plan testify to its current one.

The basement, devoted to the humungous metalwork of Richard Serra, both captivates and chills, as does the massive “Crouching Spider” (2003) by Louise Bourgeois in the attic. Yet much is also playful, or at least colorful, including Dan Flavin’s light sculptures and Fred Sandback’s string-and-wire objects. “Untitled” (1976), by Donald Judd, consists of 15 empty wooden boxes, a provocative attempt to comment on isolation; intentionally or not, they cheekily evoke the history of Dia:Beacon. From dust to dust, from ashes to ashes, from boxes to boxes.

Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art

Shabby–chic North Adams in the rural Berkshires is now home to MASS MoCA—at 13 acres and 26 buildings, one of the largest centers for contemporary arts in the world. In almost continuous use since the 1700s, the area has housed a mill, ironworks, sleigh-makers, and facilities for printing textiles and assembling electronics; products made on site were used in the Revolutionary War, in the Civil War, to make the atomic bomb, and on the moon.

Around these parts, “contemporary art” means extremely cutting-edge. Bruce Odland and Sam Auinger’s “Harmonic Bridge” (1998) creates music from vehicular and pedestrian traffic nearby. Don Gummer’s “Primary Separation” (1969) offers two halves of an immense boulder suspended 10 feet above the ground. Other sculptures and installations similarly incorporate engineering, science, and technology. Frequent events, movies, dances, and performances draw lots of crowds. A Sol LeWitt retrospective, featuring extra-large drawings, is ongoing until 2033, so no rush. If you’re into paintings that give you the warm fuzzies, you should probably keep driving until you hit the Norman Rockwell Museum, about 40 miles down the road.

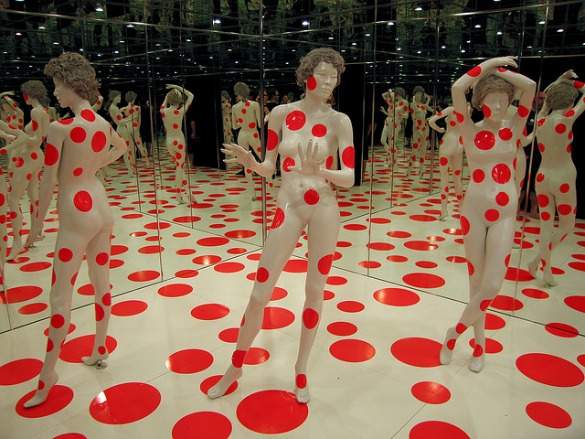

The Mattress Factory Art Museum

Permanent, avant-garde installations at this former mattress warehouse in the North Side neighborhood of Pittsburgh range from “Infinity Dots Mirrored Room” (1996), by Yayoi Kusama, in which polka dots (and the viewer) are reflected in mirrors to light projections by James Turrell. “A Collaboration” (1993) by a group of artists calling themselves Chicago Collaboration includes a periscope showing a video, water running through a handrail, and a door that cannot be opened. Many visitors rave about “Garden Installation” (1993), by Winifred Lutz, an ongoing, ever-changing study in crumbling architecture and fauna taking place in an abandoned lot next door.

You might be wondering why everything on view seems to fit so perfectly. Each year the Mattress Factory Art Museum invites several artists to live and create on site; more than 400 artists have participated since the residency program began in the late 1970s. At other museums, artists don’t always have a say in how their work gets displayed, so physical dimensions sometimes dictate how the pieces are seen, experienced, or interpreted. Here, however, artists can configure their creativity to the physics of a particular room, within a human scale. Very cool, very assertive, and far more unusual than you’d think.

santralistanbul

Newly opened santralistanbul, located on the campus of Istanbul Bilgi University, is really two museums in one. The first houses temporary exhibits of contemporary art over three floors, such as a recent display of maps, photos, postcards, models, and other ephemera devoted to examining the growth of Istanbul since the 1950s through the lens of cultural studies. The second (more fun) museum is devoted to memorializing the building as it used to be.

From 1911 to 1983, the Silahtarağa Power Plant lit up the cosmopolitan capital of the Ottoman Empire. Now the Museum of Energy, this half of the complex features the original furnaces, turbines, screws, hooks, and pipes—a plethora of fascinating, super-sized mechanical things, all coated in protective, utterly undetectable wax. The Control Room in particular looks as if workers could come back at any moment, resuming their positions in front of industrial gray-green consoles, perhaps dusting some sandwich crumbs from their shirtfronts. Go ahead and press that red button—you know you want to. Nothing will happen except the quickening of your own heart.

Tate Modern

This belligerent-looking construction on the River Thames still has the 99-meter-high chimney and brick exterior from its days as the Bankside Power Station, which supplied London with electricity from 1952 to 1981. Inside, the Tate Modern has a strong selection of twentieth- and twenty-first-century work loosely grouped by movement. The “Poetry & Dream” section, for instance, displays Surrealist highlights, such as mobiles by Alexander Calder and paintings by Max Ernst. Upstairs, “States of Flux” includes examples of Cubism, Futurism, and Pop Art by Bridget Riley and Roy Lichtenstein, among others. Due to open in time for the city’s Olympics, a much-needed expansion will encompass unused oil tanks nearby.

Especially spectacular is the Turbine Hall, cathedral-like in its proportions. Each year curators commission site-specific installations that encourage lingering or participation. On view through May 2011 is Ai Weiwei’s recently completed “Sunflower Seeds” (2010). One hundred million porcelain seeds, weighing about 150 tons, were handmade in China, then poured and spread to form a four-inch coating on the floor. Initially, visitors could walk, roll, wrestle, lay, and otherwise interact with the seeds, but the ensuing friction caused severe clouds of dust, an obvious health hazard. All things considered, though, modern art remains far less dangerous than power plants.

Photos by miriam194, Cebete, gsz/Garrett Ziegler, takomabibelot, watz, gsz/Garrett Ziegler, Dimitry B