When we open a guidebook, we open a country on paper. We know that countries are not paper, but at times we travelers who use guidebooks tend to forget that.

Before each trip our destination looms before us like a mirage. The mirage is our vision of what the destination will be like, a vision built of photographs we’ve seen or stories we’ve heard. We project images and stories onto this place we’ve never experienced, and in this way we begin building our perception of a place.

The destination itself is vague and obscured by our ignorance. Even if we think we know what it will be like, the actual experience is always much different from what we imagined.

The first step towards planning a trip to a country is often to purchase a guidebook, which will serve as our periscope into the foreign land. Guidebooks lay out what’s on offer, what things cost, practical information, cultural proclivities, and plenty of other bits of useful information, with accompanying photographs that often serve as our first visuals of the place.

When we first open a guidebook, we are laying the foundation of the country we are creating in our mind. Therefore, if we care about our perception of the world, we need to ask ourselves a few questions about this text we often use so unconsciously.

Where do guidebooks come from?

The first known travel guides for tourists appeared in ancient Greece around the second century CE. The most famous of these — Pausanias’ Guide — mentions famous places and customs that might be of interest to Greek travelers on the mainland.

Over the next few centuries travel guides written to assist pilgrims touring the Holy Land began to appear, followed by guides to the Middle East, written primarily by Egyptologists and treasure hunters.

[social]

The birth of the modern guidebook dates back to the United States in 1822, when Gideon Minor Davison published The Fashionable Tour. This was followed in 1824 by Mariana Starke’s guide to France and Italy, whose purpose was to guide British travelers on “Grand Tours” of mainland Europe. Not long after, John Murray III’s “handbooks” began to appear. These were the first guides to make use of an impersonal presentation of factual information, a style that is still adhered to by nearly all modern guidebooks.

After World War II, Fodor’s and Frommer’s guides, written for Americans traveling to Europe, first came onto the scene. Eventually they expanded their scope to cover destinations both in and outside the United States.

Over the past 30-odd years, the guidebook industry has grown to include some of the most popular travel publications today, including Lonely Planet, Rough Guides, and Let’s Go, among others.

Since the advent of the internet, the industry has been in upheaval, as “expert” travel writers are slowly being replaced by near real-time digital information provided by locals and travelers on online social networks.

How do guidebooks create destinations?

When we use a guidebook uncritically, we allow a pre-conceived, flawed version of a destination to form in our heads. If we are not mindful, our idea of this place’s past will be fashioned from the vague, heavily-edited histories provided by these books, with the destination itself taxonomically divided into its various “highlights,” which are rated according to a hierarchy developed by the authors and which we may not agree with.

Each guidebook brand has a different intended audience and thus a different approach to what it recommends. Our idea of a country will be formed by our experiences, and unless we expand our sources of information, our experience risks being formed by whatever guidebook we choose to read.

For example, using only guidebooks aimed at affluent travelers means our travels will be filtered through the lens of the affluent traveler, and seeing from this perspective will form our experiences. The India of the affluent tourist and the India of a shoe-stringing backpacker are two very different India’s. In each case, the guidebooks we choose will heavily influence our experience, as well as our memory of the country long after we leave.

Where does guidebook content come from?

The information presented in guidebooks is usually impersonal and anonymous. The index provides a list of authors, but each entry in itself is the voice of a brand and not an individual. Nonetheless, these entries are written by individuals and based (hopefully) on those individuals’ personal experiences.

As glamorous as the life of a guidebook writer may seem, the reality is quite different. A writer’s compensation is contingent on the brand and other factors, but often they are dispatched to their destination country alone and conduct their research on a very small budget. Some guidebooks writers have even complained that the cost of their trip sometimes exceeds their compensation.

Laziness and lack of incentives are two factors that should be taken into account when considering what went into the creation of the books we use to guide our adventures.

In addition to the limited funds, researching while traveling is not exactly enjoyable. A writer’s freedom is severely restricted, and the necessity to accumulate information and nuanced details wherever they go can be draining. Laziness and lack of incentives are two factors that should be taken into account when considering what went into the creation of the books we use to guide our adventures.

There may be ten accommodations listed for a particular city, but how many were actually visited by the author? How many were simply looked up on the Internet to save time and money, or given flattering or disparaging reviews due to the author’s mood? The same goes for restaurants. Are the places listed ones the author actually dined at? If so, was their inclusion in the book a result of randomly stumbling upon them, or were they simply eateries that happened to be close to their accommodation? Is the author a native of the place he or she is writing about, or simply someone in town for a day or two before moving on to the next destination?

We should also keep in mind that some writers have questionable morals when it comes to accuracy, like Thomas Kohnstamm, formerly of Lonely Planet, who authored Do Travel Writers Go to Hell? In this book Kohnstamm describes how guidebook writers like himself often make up information due to the lack of strict oversight, miniscule budgets, and rigid deadlines.

Finally, we should also keep in mind that the primary purpose of publishing guidebooks is to sell them. This leads to a tendency to “sell” a destination, as selling a destination sells its accompanying guidebook. It is no wonder then that so many destinations are described in such flattering and inaccurate language.

What impact do guidebooks have on the world?

This one is hard to measure, but there are a few points that should be explored. As often a traveler’s primary source of information is their guidebook, many tend to follow this information as if it came from the Bible.

When planning a trip, the presence of suggested itineraries in guidebooks often results in travelers designing their trip based around those itineraries. This has resulted in “backpacker trails” in various parts of the world, such as the “Gringo Trail” in South America and the “Banana Pancake Trail” in Southeast Asia. When formally quiet towns and villages are included on such suggested itineraries, it is inevitable that they will soon be flooded by hordes of penniless backpackers. In large cities this isn’t a problem, but with smaller and more traditional places, it certainly is.

Soon the personal connection between traveler and local will be gone, resulting often, within a few years, in local culture being reduced to spectacle and travelers being seen as little more than a walking dollar signs.

For example, whenever a previously “undiscovered” location is mentioned in a popular guidebook, it is likely that that location will soon be transformed, often resulting in the demise of whatever made it special in the first place. The more popular a place becomes, the more outsiders will move in take advantage of the incoming tourist dollars. Soon the personal connection between traveler and local will be gone, resulting often, within a few years, in local culture being reduced to spectacle and travelers being seen as little more than a walking dollar signs.

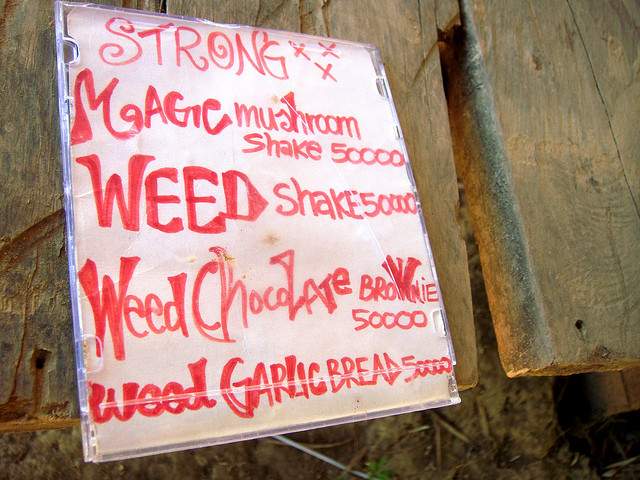

In addition to this widening rift between local and traveler, drug and alcohol abuse among locals tends to increase when backpackers begin introducing their louche lifestyle into a community.

In their native land, travelers act differently. If drugs and alcohol are occasional indulgences at home, when traveling abroad they often become everyday companions, particularly when traveling in developing countries where drugs are cheap and easy to acquire.

This increase in substance abuse while traveling impacts local culture, particularly youth culture, given that young people who seek to interact with and learn from foreigners are often introduced to these substances by travelers, often leading to the development of a drug culture among locals.

Simply put, the popularity boost that occurs as the result of a location’s appearance in a guidebook has the potential to significantly alter a place’s atmosphere and local culture.

But the religious following of a guidebook’s advice also has consequences on the travelers themselves. One thing guidebooks tend to do is de-emphasize local advice. If a guidebook states one thing and a local states another, often the traveler trusts the guidebook rather than the local, given that something printed and allegedly objective seems more trustworthy than a stranger who may be trying to swindle you. This is especially true when traveling in developing countries.

If a guidebook states one thing and a local states another, often the traveler trusts the guidebook rather than the local, given that something printed and allegedly objective seems more trustworthy than a stranger who may be trying to swindle you.

Travelers may even come to distrust local people due to printed inaccuracies. For instance, say a guidebook inaccurately lists the price of a taxi ride across a particular city. If the guidebook-listed price is one dollar and all of the taxi drivers are asking a minimum of five dollars, this might lead to the impression that all taxi drivers are out to swindle you.

Not only can this lead to the distrust of locals, but also to a false sense of assurance or fright due to an inaccurately printed statement. For instance, say your guidebook mentions inaccurately that one should watch out for thieves in a particular neighborhood. The traveler reads this and whether or not there is any actual threat of thieves in that neighborhood, the reality of the neighborhood for the traveler will be that it is full of thieves. Not matter how beautiful or safe the neighborhood actually is, thieves will saturate one’s thoughts while in it.

There are also instances of following a guidebook’s advice that have led to harm. One example is Johan Lundin, a Swedish tourist who in 2012 died after drinking a mojito made of methanol in a bar in Indonesia. He had been following Lonely Planet’s recommendation of the obligatory mojito at that particular bar.

A more variegated approach

So far this article has been quite critical of guidebooks, but I’m not arguing that travelers should discard them completely. Guidebooks offer invaluable information to help guide and plan a trip, and some contain in-depth, insightful cultural and historical information.

Rather, the point of this essay is to remind travelers that the guidebook is a flawed document whose existence and usage has consequences. Conscious travelers should question the information guiding them, be aware of that information’s sources, and compensate for the guidebook’s flaws by using a variety of publications, both online and in print.

Unlike the previous generation of backpackers, we now have one of the greatest traveling tools ever devised — the internet. For planning a trip, the internet is truly invaluable, particularly since the emergence of websites such as Wikitravel and Tripadvisor, which offer users’ reviews and descriptions of accommodations, restaurants, and tourists sites. Tripadvisor, in particular, is a great way to gather up-to-date information about the best local restaurants rated and reviewed by those who have actually eaten there.

Every person you meet along the way is a country in themselves, with a personal history often as vast as the places we so blindly drift to one after the other.

The web is also an invaluable source for obtaining information from locals and travelers who’ve been to the places you’ll be visiting. Two of the best platforms for obtaining this sort of information are various travel forums like here at BootsnAll, couchsurfing.org, and the Thorntree forums on LonelyPlanet.com, where a surprisingly devoted group of people is ready to answer nearly any travel-related question. Also, rather than relying on the outdated accommodation reviews in guidebooks, try using websites like hostels.com or hostelworld.com, which offer a customer-reviewed selection of cheap accommodation with real-time prices.

Finally, deviation from the established trails recommended by guidebooks is important for those seeking truly unique travel experiences. The anxiety that results from “missing out” on the highlights named by the guidebook should be ignored unless the aim of your travels is simply to sightsee while being constantly surrounded by other travelers.

If you’re seeking to step out of this mold, simply journeying to “exotic” or “unexplored” locales is no longer going to cut it. You’re going to have to be more creative than that. Regardless of how many people have walked the same journey you’re now walking, there will always remain room to experiment with how you walk it. There are always side paths, hidden to those in a hurry, which discerning and deliberate travelers will find or create for themselves. And these paths don’t necessarily have to be physical. Every person you meet along the way is a country in themselves, with a personal history often as vast as the places we so blindly drift to one after the other.

It is in the nuance of the experience, not in books, not in geography, where the best journeys are to be found.

The possibilities of discovery are inexhaustible, but if it is true discovery you want, you cannot expect to find it in a guidebook, or any book. In books all you will be given is what is known. It is in the nuance of the experience, not in books, not in geography, where the best journeys are to be found.

For more on guidebooks and travel resources, check out the following articles and interviews:

- Indie Travel Interview: Rick Steves

- How I Travel: Tony Wheeler

- Ditch the Guidebook: 8 Alternative Trip Planning Resources

- Rethinking Traditional Travel: 7 Tips to Break the Mold

- How to Use a Guidebook Without Letting it Ruin Your Trip

How important are guidebooks to your travel planning? Comment below to share your thoughts.

Photo credits: Pinguino, Jaymis, jonrawlinson, Hotel Duquesa de Cardona Barcelona,