Further Listening: Rolf Potts and BootsnAll Co-Founder Sean Keener discuss in this podcast how travel has evolved

Twenty years ago, when I set off on my first multi-month vagabonding trip around Asia, I noticed that a lot of the backpackers I met – cool indie travelers from places like Denmark and Tasmania and Oregon – were fixated with the notion of what travel must have been like in the 1970s. Indeed, as enjoyable as Thailand and India and Japan were in 1999, there was this sense that we had missed out on an earlier, purer era of travel some two decades before – a time before the advent of dial-up Internet cafés and international phone-cards and backpacker-ghetto street-kiosks that sold bootleg Fatboy Slim cassettes.

Earlier this year, when I arrived in Sumatra on what was to be the first leg of a 20-year vagabonding-anniversary tour across Asia, I had trouble wrapping my head around the wonky math that can frame the passage of time. In 1999, the very notion of 1979 felt as antique and faded as an Instamatic photo-print from that era – yet to my 2019 self, 1999 still feels like it wasn’t all that long ago. Sure, dial-up Internet connections are ancient history (as is the notion of using a plastic tape to access your music, or a plastic phone-card to call home), but is the way we travel today really all that different than the way we traveled two decades ago?

Is the way we travel today really all that different than the way we traveled two decades ago?

One month into my journey, my answer to that question is – perhaps inevitably – “yes and no.” No doubt an indie traveler in his or her twenties might view 1999 in the archaic, romanticized sense that my twenty-something self once regarded 1970s-era travel – but on-the-ground reality feels more nuanced than that.

In a certain sense, the giddy excitement that accompanied the early days of my 2019 journey felt nearly identical to the emotions I felt at the outset of my 1999 trip. I’ve been savoring the humid air and unfamiliar smells that come with a visit to this part of the world – the ongoing rituals of problem-solving and self-education, the enforced patience and simple English and newly learned phrases required to get around. I’ve also found familiar joy in the notion that independent travel can blow your days wide open, if you allow it to – giving you options but not prescriptions, enabling you to walk (or ride a bus, or sit still) in a new place until your day becomes interesting.

For all of the visceral similarities to my earlier journeys, however, my first month of travel in 2019 has cast an interesting lens on what I experienced in 1999.

Here are five key similarities and differences to what I experienced two decades ago:

1) Indie travel has gotten easier, in ways that can enhance the journey

About a week after embarking on my winter journey through Asia, I wrote the following passage in my journal: “More than steak or bourbon I am dying for a decent map to Sumatra.” Indeed, as much as I enjoyed riding a rental motorbike in the highlands outside the Sumatran hill-station town of Bukittinggi, my journey was complicated by the fact that road signs could be hard to decipher and paper maps to the area are sorely lacking in detail.

This all came to a head when I took a wrong turn near the volcanic shores of Lake Maninjau and rode halfway to the Indian Ocean before realizing that I was no longer following the lake road. This presented an interesting conundrum: Should I turn back to the beauty and certainty of the lake road, or strike out into the unknown?

There’s a reason why travelers tend to end up at the same awesome spots (such as the Lake Maninjau road), but isn’t travel also about the serendipity of the unexpected?

It was while wrestling with this conundrum (still wishing for a detailed paper map of the area) that I realized I had downloaded an iPhone app called maps.me a couple of years earlier. I’d always been too stubborn to use it, but – recalling that its navigation function worked offline – I opened it up and began to search for which road I was traveling. Within seconds I knew not just what road I was on, but where exactly I was on that road, and what other roads were reachable within a 20-mile radius. In a moment, I was thus able to see what awaited me in all directions. Sensing that the coastal road would be a bottleneck, I headed inland, circumnavigated the lake, and rode up a nearby mountain-ridge, which offered a gorgeous view of the caldera below.

I have since related this story to several younger travelers, who have pointed out that for less than $10 I could have bought an Indonesian SIM card for the month and used any number of live-data navigation apps as well. I tend not to buy local SIM cards for the simple and (and faintly cantankerous) reason that I got along just fine without live data 20 years ago.

That said, my stubbornness hasn’t extended to the two-dozen or so travel-friendly apps I use in wifi or offline situations: Google Translate and Duolingo for language reference and learning; WhatsApp and Skype for making onward arrangements or calling home; the XE currency app for calculating exchange rates; TripScout or Lonely Planet for planning city travel; iPhone notes and voice memos for field reporting; Instagram for broadcasting glimpses of my journey in near-real time. Not to mention mobile-banking apps to manage my finances, Apple Podcasts and Netflix to entertain myself during long airport layovers, and even Sky Guide to clue me in on which equatorial constellations I’m seeing at night.

2) Indie travel has gotten easier, in ways that can limit the journey

While smartphone apps can make travel easier in many ways, however, they can also get in the way of an organic travel experience.

I’ve often said that three big gifts of travel are the opportunities it offers a person to be lost, lonely, and bored – and smartphones have made these counterintuitive travel-blessings easier and easier to avoid.

Sure, the reality of being lost or lonely or bored can be dispiriting, but these situations have a way of challenging us to push our comfort zones – and getting out of your comfort zone has always been a key step to achieving serendipity and self-discovery on the road.

Twenty years ago, for example, without maps.me at my fingertips, I might have pushed myself to explore the less-backpacker-friendly ocean road rather than turning back for the lake road (or at the very least I would have stopped and chatted up local people for advice).

Moreover, while I’ve been encouraging folks to work through their lost-ness, loneliness, and boredom for the past two decades, I’ll confess that I have at times cheated on these very principles during my first month here in Asia. I have not only listened to podcasts and watched Netflix downloads in airports – sometimes I’ve indulged in these diversions in my guesthouse when I could have been out finding local Indonesian entertainments. Other times I’ve burned off those same guesthouse-hours replying to Instagram comments or texting people back home when I could have been out chatting with Sumatrans, or other backpackers.

In pointing this out I’m not saying that it’s bad to assuage boredom and loneliness with your smartphone. I’m just noting that these are the same workaday strategies we use to kill time at home – and travel, at its best, is about embracing rather than killing time.

Travel is about engaging your immediate environment; it’s about living in the moment rather than compulsively pulling up a screen every time you feel uncomfortable.

Smartphones – and smartphone apps – have literally been engineered to make us think we need them. The key, on the road, is to find ways to use them without letting them distract us from what is right in front of our eyes.

3) Photos have become an irrevocable part of how we travel (and that’s OK)

Twenty years ago, during that first vagabonding journey across Asia, I traveled with a point-and-shoot film camera. Given the expense and inconvenience of buying and developing film along the way, I rarely shot more than 2-4 rolls of film per month as I was traveling. That shook out to about 12-24 travel-photos a week – which is far fewer images than I average on a typical afternoon of using my iPhone camera. Taking travel photos in 2019 has become so easy – and so central to my narrative sense of the journey, even as a writer – that the frugal conservatism of my 1999 photo habits can seem a bit peculiar in retrospect.

Back at the turn of the millennium, however, conventional travel wisdom asserted that constantly taking photos was at odds with the experience of travel itself – and the spectacle of a camera hanging from the neck of a middle-aged man in a floral-print shirt was cartoon shorthand for “obnoxious tourist.”

As Susan Sontag had noted in her 1977 book On Photography, “the very activity of taking pictures assuages general feelings of disorientation that are likely to be exacerbated by travel. Most tourists feel compelled to put the camera between themselves and whatever is remarkable that they encounter. Unsure of other responses, they take a picture.”

Two generations after Sontag wrote this, there isn’t much of a debate left on the role of photography in travel: With few exceptions, photos have become central to how we all see our journeys. This is in part because our travel-photo habits have become an inevitable extension of a more general photo-mania that applies just as well to the lives we lead at home.

I was constantly reminded of this in Sumatra by the very fact that the Indonesians who lived there seemed to be taking as many smartphone photos as I was. Twenty years ago, asking a local person to pose for a photo in a place like Southeast Asia was a one-way endeavor that required courtesy and care. In 2019 people in places like Indonesia are so used to posing for each other’s photos that they invariably thrill at the novelty of mugging for an outsider. I’ve lost count of how many times I have myself been asked to pose for exuberant, slightly blurry selfies with groups of Sumatran teenagers.

I was constantly reminded of this in Sumatra by the very fact that the Indonesians who lived there seemed to be taking as many smartphone photos as I was. Twenty years ago, asking a local person to pose for a photo in a place like Southeast Asia was a one-way endeavor that required courtesy and care. In 2019 people in places like Indonesia are so used to posing for each other’s photos that they invariably thrill at the novelty of mugging for an outsider. I’ve lost count of how many times I have myself been asked to pose for exuberant, slightly blurry selfies with groups of Sumatran teenagers.

4) Indie travel is still crazy cheap (if you go to inexpensive places)

When my book Vagabonding came out 16 years ago, I noted I’d kept my travel-expenses down around $1000 a month when I’d wandered through inexpensive regions like Southeast Asia and the Middle East. Readers have occasionally contacted me to ask if – all these years later – this shoestring budget-estimate still holds true. After a month in Indonesia, I can say that the answer is “yes.” Having tallied my expenses, four weeks in Sumatra cost me around $1200 – and that includes a Padang-Medan domestic flight, three nights in airport hotels, ATM fees, a five-night guided trek in the Mentawai Islands, and a $20 fine for overstaying my Indonesian visa by one day.

The best part is that I didn’t travel this cheap by resigning myself to long-haul chicken-buses and dirt-bag backpacker hostels (not that there’s anything wrong with either of those things). At Lake Toba – a gorgeous volcanic caldera in north-central Sumatra – I paid $11.75 a night for a private room with a balcony just a few feet from the shoreline. At Lake Maninjau I paid $12.50 a night for a cottage ten steps from the deep-blue water. At Rimba Eco-Lodge – a beautiful stretch of wilderness-beach one hour by boat south of Padang – I paid $18 for three meals a day and a private room 90 seconds from a reef full of butterflyfish and sea turtles. My best value in Sumatra, however, was a lotus-pond-fringed cottage two minutes from a sheer-cliff waterfall in the Harau Valley that cost me $8.50 a night, breakfast included.

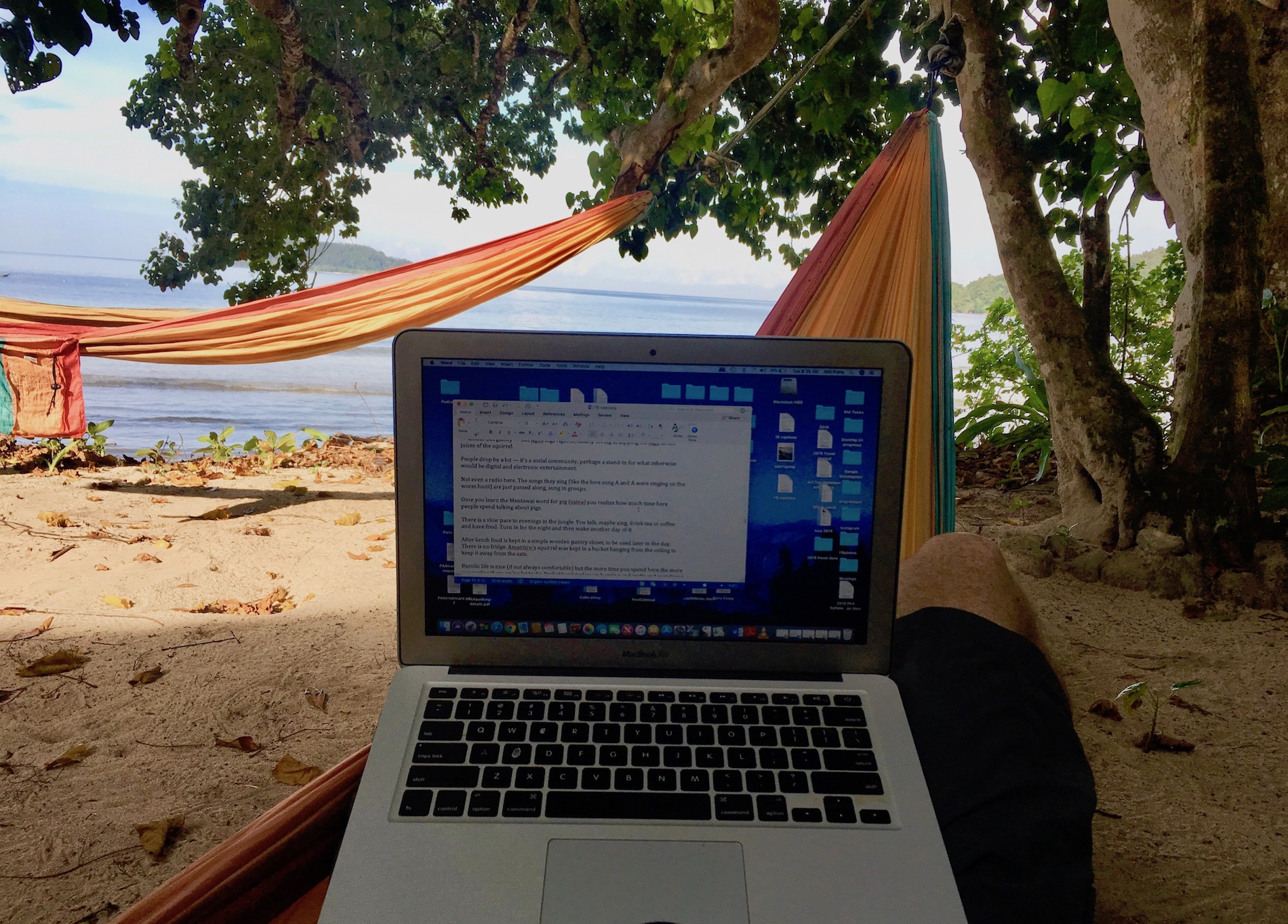

This said, the stunning vistas and bargain prices at these places involved a bit of hardship and sacrifice. The budget-friendly guesthouse rooms I mention here were pretty basic, and often all I got was a bed, a mosquito net, an outlet to recharge electronic devices, a cabinet (or wall-hooks) for stowing my gear, a porch hammock for afternoon reading and naps, and a cold-water bathroom. My lotus pond cottage in the Harau Valley didn’t have hot water, though considering this part of Sumatra is about ten miles from the equator I can’t say this was a problem.

Itinerant travel aside, Indonesia is the kind of place you might visit just to chill out in a single beautiful place and recharge for a month or two: swimming in a lake (or the ocean) each morning; going for long hikes or motorbike rides; learning a bit of the local language and culture; eating healthy; waking up with the sun and turning in early; sitting in a hammock and reading all the books you’ve been meaning to read. All for a fraction of the price you’d spend on food, entertainment, and rent/mortgage back home (let alone a commercial tourist resort in some other, high-traffic part of the tropics).

5) Most places in the world have not been “discovered”

These days it’s common to see pessimistic news reports of mass-tourism overwhelming certain beloved destinations – of tourists pricing out locals in Venice, of Game of Thrones fans clogging up the streets of Dubrovnik, of Instagrammers bickering over selfie-space at the Taj Mahal, of Machu Picchu limiting tourist access at certain times of the year, of Thailand indefinitely closing Phi Phi Island’s Maya Beach so it can recover from two decades of over-visitation.

Even the fabled ends of the earth – Antarctica, the Galapagos, the Nepal approach to Mount Everest – have struggled to deal with increasing numbers of visitors over the course of the past 20 years. These articles invariably point out that the travel-world has been “discovered,” to the detriment of the very places we dream of visiting.

Having just spent a month visiting Sumatran landscapes that rival the splendor of anything I’ve seen elsewhere in Southeast Asia, I have to assert that – contrary to the alarmist tone of these articles – the world isn’t close to being “discovered.”

Sure, ten dozen marquee destinations around the world will continue to face the challenges of dealing with mass tourism, but part of the solution here is to seek quieter, just-as-enchanting places that, by their relative anonymity, never land on your average traveler’s bucket list.

Tourism to the Indonesian hotspot of Bali has boomed over the course of the past two decades (resulting in high-season water shortages and traffic jams), yet Bali is just one midsized isle in an Indonesian archipelago that encompasses thousands of beautiful and culturally distinctive islands. The beaches, rice terraces, indigenous cultures, and surf breaks of Sumatra in many ways rival (or even exceed) those of Bali, yet I spent a month there and rarely crossed paths with tourists beyond a handful of backpackers, surfers, European retirees, and Indonesian vacationers.

Which felt strange to me, since 20 years ago Sumatra (and Lake Toba in particular) was a popular stop on what was then called the “Banana Pancake Trail” – a string of scenic, sleepy backpacker-friendly destinations that stretched across Southeast Asia. Sumatra had garnered a reputation as a challenging-yet-blissful stepping stone on the overland route from Bangkok to Bali – but with the recent rise of budget airlines, many backpackers now choose to fly to directly to Bali from Singapore and avoid Sumatra’s lousy roads altogether.

Travelers willing to embrace the inconvenience of places like Sumatra will find a wealth of less “discovered” destinations most anywhere in the world they wander.

Moreover, it’s worth mentioning here that the very compulsion to declare that a place has been “discovered” is pegged to an outmoded way of thinking that hasn’t been relevant in more than a century.

Indeed, throughout the so-called Age of Exploration, colonial-era adventurers had a knack for “discovering” things that local populations had known about for hundreds of years.

A better way of thinking about exploration, I’d reckon, is to frame it on a more personal level of awareness and receptivity – of learning to pay attention and improvise your way into new directions, regardless of what was on your bucket list when you left home.

Other Rolf Potts Content