Flying out of San Francisco’s Airport, Madagascar is about as far away a person can get. Once here, the lack of tourists, expats, and large international chains, combined with a totally unique ecosystem and culture gives off an air of visiting somewhere forgotten, remote. It epitomizes the ever coveted off-the-beaten-path travel destination.

Unfortunately, its inaccessibility has created a tourist industry that caters more to tour groups and wealthy independent travelers willing to rent private cars and personal guides. As such, independent backpackers who can’t afford this luxury, choosing instead to traverse the country’s roads by public transportation, eat local, and take things as they come are a rare yet admirable sight.

“It epitomizes the ever coveted off-the-beaten-path travel destination.”

Exploring Madagascar as a backpacker is a mixture of rewards and hurdles, but knowing a bit about the country before venturing into the bush will help the adventurous minority have a more trouble-free journey.

Navigating Public Transportation

Traversing by Taxi-Brousse

Fasankarana, the southern bus terminal in Antananarivo, is a chaotic, muddy, traffic-jammed sprawl of buses and wooden shacks. As soon as to-be passengers arrive, groups of hawkers immediately rush up, berating them with names of towns, grabbing bags, and trying to lead them to whichever bus (taxi-brousse in Malagasy) or company they are working with.

Some even hop into still moving taxis, coyly asking “Vous-allez ou (Where do you go?)?” All the meanwhile, cars honk, babies cry, women with baskets full of food or knick-knacks on their heads hawk their wares, and if you have the misfortune of a recent rainstorm, the whole place becomes a pungent muck of mud- and who-knows-what puddles.

“If you find yourself here, don’t panic.”

If you find yourself here, don’t panic. Breathe. This will (hopefully) be the most difficult part of your journey, the most difficult taxi-brousse station you visit.

Once at your bus or ticket-counter, be warned that bus companies will frequently over-charge foreigners, quote fares in Francs instead of Ariary (1 Ariary = 5 Franc), or wrongly demand extra for luggage. In addition, it’s suggested to make reservations for longer bus journeys but not to pay in full for your ticket up front.

On the Road

You have your ticket, you’re on the road. Survive long bus rides by keeping a small bag with all valuables and travel essentials with you, even bringing it inside when the bus stops for meals to prevent theft. Sleeping pills, toilet paper, hand sanitizer, snacks, a sweater, and a sarong for women (for when there is no “decency bush”) are packing musts. Food and water can be bought along the way, and long-bus rides always make regular meal stops.

“Survive long bus rides by keeping a small bag with all valuables and travel essentials with you…”

Warning: As of summer 2012, a group of cow-thieves known as “Dahalo” (da-ha-lu) have become more active on the road between Fianaratsoa and Fort Dauphin in the southern part of Madagascar. Those wishing to travel to Fort Dauphin overland should avoid the road between Ihosy and Fort Dauphin, and if weather allows travel down the east coast from Manakara instead. Ask locally for updates on this situation.

Local Transportation

Local transport varies greatly from city to city, but you can generally expect a combination of pousse-pousses (rickshaws), taxi-cabs, and buses. Buses typically cost around 300AR ($0.13), while a pousse-pousse tends to be around 1,000-2,000AR (~$0.50-$1.00)– depending on distance. Always bargain with your pousse-pousse or taxi driver.

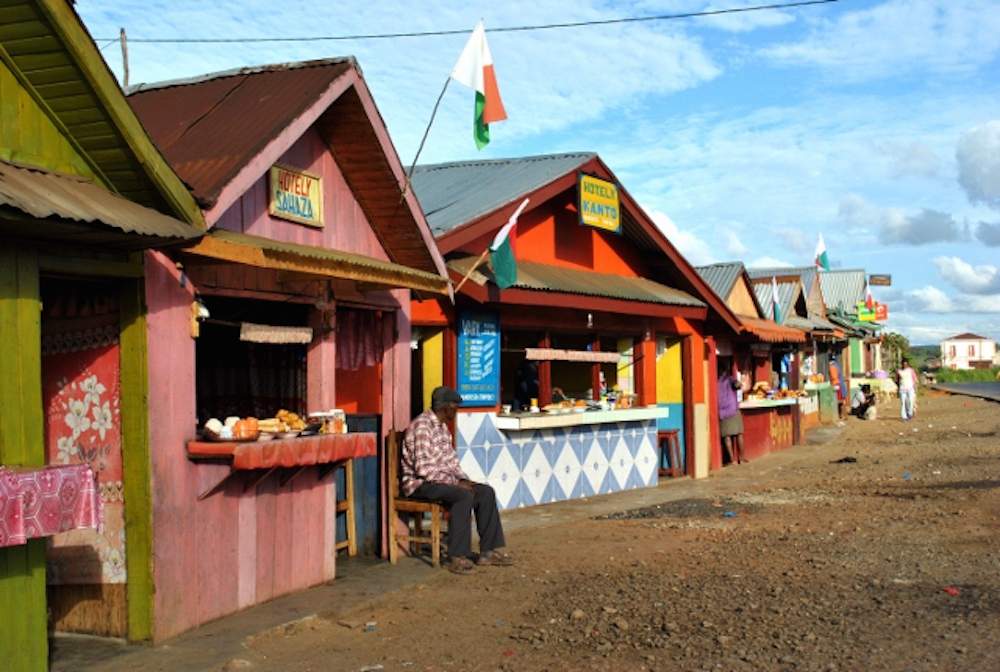

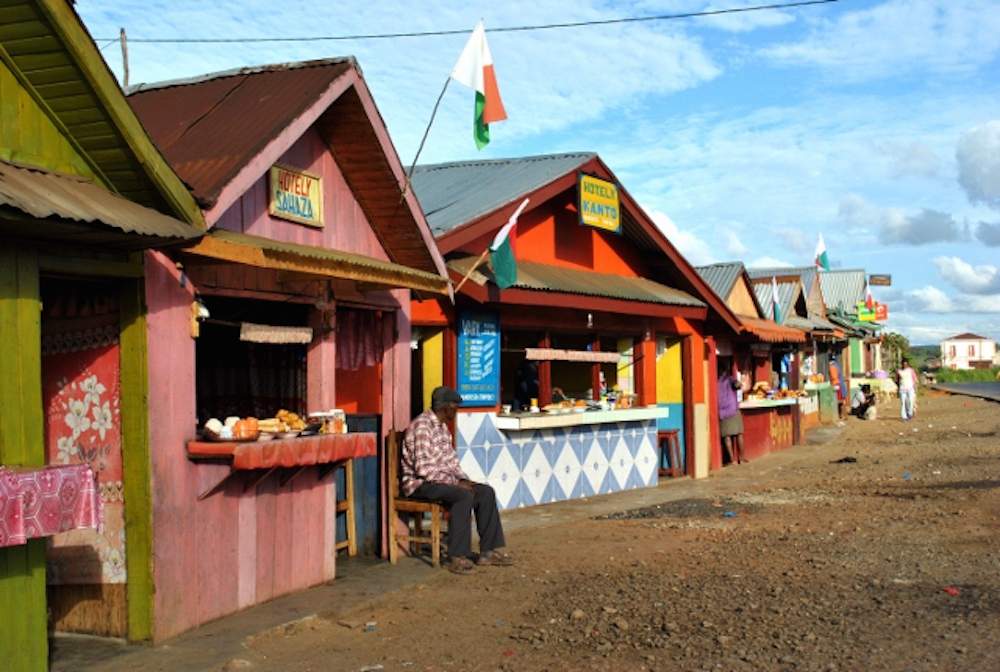

Spotting a Local Eatery

Hungry and tired of walking, I entered a home-styled Malagasy hotely, or restaurant, outfitted with about five tables neatly covered in plastic tablecloths. A glass display case sat in the window, showing off all the typical snacks – potato salad, pasta salad, and shredded carrots and cabbage in a vinegar dressing. But I craved something filling, which in Madagascar means only one option: rice.

As the highest per capita consumers of rice in the world, a meal at a Malagasy home or hotel inevitably implies receiving a bowl of plain rice the size of your head, and a smaller bowl of “loaka” (loh-ka), which roughly translates as “side dish” or “the thing you eat with your rice.” Later in my lunch, an elderly gentleman would proudly announce to me “Malagasy eat rice three times a day! We’re not full if we don’t eat rice,” further reiterating the cultural importance of rice in Madagascar.

Within seconds of sitting down, a middle-aged woman with a worn but freshly pressed Outback Steakhouse apron came over to my table.

“Do you have rice?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“What’s the loaka?”

She pointed to a blackboard near the door. Hen-omby sausy, beef with sauce. Hen-kisoa sy tsaramaso, pork and beans. Hen-akhoho sy petit-pois, chicken with peas.

“Just peas, please. I’m vegetarian.” I finally decided.

As her menu demonstrated, Malagasy do comfort food well. They rarely get daring with food and generally keep dishes hearty, fresh, and simple. Each region has a slight variance on the rice-and-loaka, like the North coast’s abundance of coconut rice and fresh crab, and all cater well to vegetarians. Malagasy food is also quick. I barely had enough time to send off a text message before rice, peas, a bowl of broth, and a steamy mug of ranonapango (rah-na-na-pahn-gu) – a hot, rice tea with a subtle, popcorn-like flavor, piled up in front of me.

“As her menu demonstrated, Malagasy do comfort food well.”

“Mazatoa! Enjoy!” the woman said with her final, flourishing placement of a salt and pepper caddy at the center of the table, satisfied that every detail of presentation had been accounted for.

Trekking & National Parks: Do I Really Need a Guide?

While teaching an ESL course to guides in Andringitra National Park, home of the highest accessible peak in Madagascar (Pic Boby), all ten or so backpackers I met invariably asked the same question “Do I really need a guide? They’re kind of expensive.” The answer, unfortunately, is yes. Trails are vaguely marked, and without a guide it’s easy to get lost. However, the money that goes to guides is a huge support for their families, and at least in the case of Andringitra, a portion of it goes back to the community for things such as building pumps or repairing roads.

““Do I really need a guide? They’re kind of expensive.” The answer, unfortunately, is yes.”

If you are looking to save money on visiting national parks, usually the biggest chunk out of a backpacker’s budget, try opting for day hikes which cost less than overnight treks. Most of the time, there is a park office near the entrance where you might be able to pitch your tent (although they may charge around $5USD) instead of paying for a hotel room.

Moreover, not all parks cost the same. For example, tourist-heavy Ranomafana, on the road from Fianaratsoa to the East coast, costs more than it’s northern neighbor, Andasibe (between Antananarivo and Tamatave), but both offer rainforest and night-hikes to see nocturnal lemurs. Similarly, tourists tend to pay more for shorter hikes in Isalo than hard-to access Andringitra, but both parks offer stunning vistas totally unique to their area. Choosing one over the other depends entirely on individual preference – do you want to do a 3-day trek or have you only got enough energy for a couple hours?

“In the end though, experiencing Madagascar’s incredible nature…is not something to skimp on.”

In the end though, experiencing Madagascar’s incredible nature – from Morondava’s Avenue of Baobabs in the west, remote beaches and spiky rock forests, called tsingy, that dot the north, and all the heartwarmingly adorable lemurs in between – is not something to skimp on. Go where most intrigues you and revel in the fact that no place else on earth may look the same as where you are right now.

Crash Course in Malagasy Customs

In the Oscar-nominated short

Madagascar, carnet de voyage, the lone white backpacker enters a Malagasy village and the words “all eyes on me” flash across the bottom of the screen. True to life in Madagascar, the film characters smile, shout “eh, vahazah!” (“foreigner!”), or they simply stare. After a while, all this attention can make a person feel like a novelty, objectified, or just plainly annoyed. However, the true nature behind their reactions to a foreigner sauntering about town is generally innocent curiosity. “We only see white people in films,” one Malagasy woman from a rural village admitted, “so when we see them in person, it’s like seeing a celebrity. We just want to know more about [them].”

But it’s not just curiosity. Malagasy find it flattering that someone should choose to visit Madagascar, and that, combined with a strong set of cultural norms for receiving guests (such as gestural gifts of rice or giving you the honorable “guest chair” at a dinner table), makes it an incredibly warm and welcoming country to visit.

“Malagasy customs rooted in their traditional belief system that works alongside modern Christian institutions. “

Digging deeper into Malagasy culture, foreigners will find the most unfamiliar and captivating of Malagasy customs rooted in their traditional belief system that works alongside modern Christian institutions. The most noted is the famadihana, or turning of the bones. During these several-day-long parties, typically held in the colder months of June through September, friends and families gather to move the bones of ancestors from a temporary tomb to a final, more ornate, resting spot. If invited, it is customary to give the hosting family a small envelope with a couple thousand Ariary on behalf of your party.

Most places also have local taboos, or fady (fah-dee). For example, visitors can’t bring pork into Andringitra National Park. Other towns won’t farm on a specific day of the week. And fortunately for the environmentalists of the world, eating lemurs is another common fady. Visitors should ask about and respect them. “In one island up north,” a Malagasy friend recounted, “it is fady to take a boat in the ocean on Thursdays, but one French family didn’t respect this and their son fell into the ocean and almost drowned.” We might think some fadys silly, but Malagasy certainly take them seriously.

“Most places also have local taboos, or fady (fah-dee)… Visitors should ask about and respect them.”

Ultimately, there will always be unavoidable hiccups and a whole host of discoveries that make them worthwhile. But as the expats of Madagascar say, “It may take longer than expected to get where you’re going, but you’ll always get there in the end.” Smile, and enjoy whatever comes in this little-explored pocket of the globe.