We use travel idioms like it’s all Greek to me and shoe-string budget every day but do you ever stop to wonder what they mean? What’s a shoestring? And why do we travel through South-East Asia on one? The following are origins – and explanations – for 15 popular travel words and expressions.

Travel

What we consider to be a painful travel experience nowadays usually don’t involve much more than a long wait in the security line at the airport, a crowded flight or jet-lag. But for our nomadic ancestors, the hazards of travel not only involved weeks of walking on unpaved roads, but the threat of run-ins with wild rhinos or robbers, as well. Perhaps it’s not surprising then, that the word travel can trace its roots back to an ancient instrument used for torture.

According to the book Word Origins, by Dhirendra Verma, the word travel comes from the French word travail which means agony or torment, a word taken from the Latin, tripalium. Long ago, torture victims were tied to a tripalium (a three-staked apparatus) and then set on fire. The fact that early travelers named an experience many today consider a leisure activity, after a torture device, suggests that they weren’t exactly burning with a desire to hit the road any time soon.

>> Even now, travel isn’t always easy. Read about common travel disasters and how to cope with them.

[social]

Long Time No See

The expression “Long time no see” is now such a common addition to the English lexicon that few may even notice that grammatically-speaking, it’s completely nonsensical. According to the book Clichés, by Betty Kirkpatrick, this is because this greeting isn’t rooted in English grammar at all, but rather, Chinese. The phrase is thought to have been introduced into American English by Chinese immigrants in the 19th century. These early English language-learners likely applied Mandarin grammar to the phrase “It’s been a long time since I’ve seen you!” and long time no see was the result.

Tourist

Often seen as culturally insensitive and demanding, tourists have long harbored a bad reputation with local populations the world over. But surprisingly, this isn’t a reputation that’s developed over the last three decades, but rather, over the last three hundred years, beginning in 18th century Europe.

The word tourist, which means “one who tours'” was once strictly reserved for wealthy aristocrats. The sons of British royalty, according to Michael Quinton, author of the book Port Out, Starboard Home: And Other Language Myths and the website World Wide Words, were frequently taken on a Grand Tour of Europe “as a kind of extended finishing school.” While these tours were designed to provide a rich cultural experience, they usually involved more visits to the local brothels and gambling halls than they did cathedrals or castles.

Similar to the European backpacking trips taken by young students or gap-year travelers today, these Grand Tours were seen by the young royals as a final chance to paint the town red before they had to settle down into a career or marriage. Not surprisingly, their drunken debauchery didn’t earn them a favorable impression with the locals and thus the ugly stigma of a tourist, was born.

>> We think the “tourist vs traveler” debate should be retired. Read about other stupid travel arguments and why we should stop having them.

When in Rome, Do as the Romans Do

As far as etymologists can tell, this phrase was first coined by the Christian Saint Augustine in a letter he wrote to the Bishop of Naples. As is outlined in the website The Phrase Finder, Saint Augustine advised the Bishop to adapt to local customs when visiting parishes in neighboring cities because this would avoid possible scandal or embarrassment. He cited an example of how while he didn’t fast on Saturdays in his native Milan, he did when visiting Rome. How a phrase coined in a single letter written between two friends in Italian in 390AD could have found its way into English by the Middle Ages and now, centuries later, be so common it borders on cliché, is nothing short of incredible.

>> What do the Romans do? Read about ten things to do in Rome.

Hobo

Hobos first came into existence in the US after the Civil War but really made a name for themselves after the Great Depression, when the numbers of train-hopping travelers in the United States grew significantly. A lack of money and jobs forced workers, according to Evan Morris, author of the column and website “Word Detective”, to abandon their homes and hit the rails in search of work.

Where the term hobo comes from still remains a mystery to etymologists, but they have their theories. Morris suggests that it originated with “Ho, boy!” a greeting railway or migrant workers may have shouted to one another over the train tracks. Hobo also could have been short for ‘hopping boxcars’ or even Hoboken, NJ, which, in those days, was one of the nation’s central train crossings.

Hitchhike

The earliest form of hitchhiking was said to have originated in the 19th century in the United States. According to the book Word Origins, when two men needed to venture somewhere but only had a single horse between them, they’d compromise by alternating who got to ride in the saddle. One man would ride the horse for a time and then dismount, hitch the horse to a tree and continue the journey on foot. When the second man eventually caught up to the horse after his hike, he’d unhitch the horse and ride until he’d surpassed the man traveling on foot. Both men would alternate hitching a ride on the horse and hiking until they reached their destination.

>> Get tips for hitchhiking in Southern Africa

The Boon Docks

No one ever wants to get stranded in the boon docks (or the ‘boonies) and certainly least of all the American soldiers who popularized the word during the Vietnam War. As Morris detailed in his column, the word boon dock originated from the Tagalog word bundok, which means mountain. To those living in the Philippines, the mountains were located inland, away from the cities along the coastline and thus, in the middle of nowhere. Although bundok was first introduced into English in 1909, it didn’t surface as a common slang word until it was adopted by the American soldiers stationed in the Philippines in the 1930’s and 40’s.

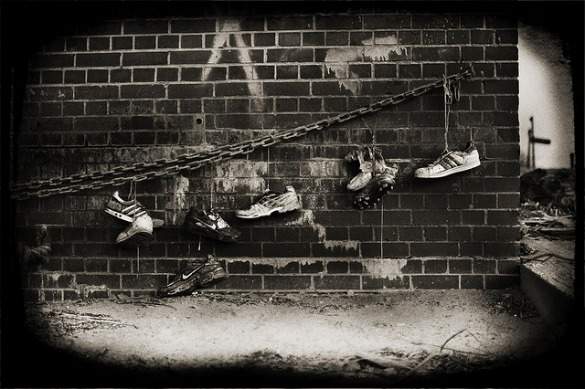

Shoestring Budget

Etymologists are still tied up over the exact origin of the idiom shoe-string budget. The easiest explanation would be that the phrase came about because shoestrings (an old word for shoelaces) were one of the few inexpensive items New York City’s poor immigrants had to barter with or sell in the beginning of the 20th century. Thus, surviving off a shoestring budget, according to author Michael Quinton, could have been taken quite literally.

Another theory that the American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms offers up, places the origin of shoestring budget in British prisons. Prisoners were thought to have used their laces to dangle their shoes out of cell windows, in the hopes that passerby would toss in their spare change. They were definitely living on a shoestring, or rather in one, as Jonathon Green reports in the Chambers Dictionary of Slang. Begging in this fashion was reportedly so common in England’s Newgate Prison, that one of the prison’s wards was nicknamed “The Shoe.” While this explanation makes for an interesting story, author of The American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms, Christine Ammer, cautions that it’s likely nothing more than a “fanciful theory.”

>> What’s the dollar equivalent of a shoestring? Find out how much money you really need to travel.

Flying By the Seat of One’s Pants

Flying by the seat of one’s pants is an expression first made popular during World War II. Today it’s used to describe a situation in which a person acts without prior preparation or assistance; thus relying solely on his own wits or intuition for survival. While flying by the seat one’s pants is certainly a skill many modern travelers rely on today (try haggling over a taxi fare in Morocco or Malaysia without it) the first travelers to coin the phrase were actually 1930’s British pilots. According to Morris, the navigation equipment (compass, speedometer, etc.) in early airplanes would frequently fail and pilots would be forced to fly using not much more than the vibrations in their seat in order guide to guide their planes to safety.

Neck of the Woods

When early American settlers first arrived on the shores of New England, they discovered that much of the land was covered in forest. Needing plots of land on which to build their homes, but not wanting to have to chop down large sections of the forest in order to build them, they searched for natural clearings. And as Quinton explains, what they found were long, narrow strips of treeless land that looked not unlike the neck of an animal. Asking someone “Where’s your neck of the woods?” therefore meant the same to the pilgrims as “Where’s your neighborhood?” does to Americans today.

Three Sheets to the Wind

Some may travel to far off places to explore ancient ruins, to visit natural wonders or simply to experience a culture vastly different from their own. Others travel in order to temporarily escape their troubles, forgoing a tour of the Taj Mahal, for instance, for a tour of the tequila factory. Spring Breakers and Booze Cruisers around the world can certainly appreciate how sometimes, travel and drunkenness can go hand-in-hand, hence the inclusion of three sheets to the wind to this list.

Like many English idioms in use today, three sheets to the wind takes its meaning from a nautical term used by sailors and pirates during and prior to the early 1800s. As Quinton clarified on his website, World Wide Words, a sheet is a reference to the rope that sailors once used to secure a sail. If a ship’s sheets were loose, the sails would flap around in the wind and the ship would rock back and forth, not unlike the unsteady gait of a drunken sailor.

>> Read about places where drinking is part of the cultural experience.

It’s All Greek to Me

According to Quinton, It’s All Greek to Me owes its heritage to the medieval Latin proverb: “Graecum est; non potest legi” which translates into “It’s Greek. It can’t be read.” English speakers often used Greek as the go-to language for any speech that they couldn’t understand, as did the Spanish who also used a similar expression, “hablar en griego.”

Visit any Latin American country today and you’ll likely hear the word gringo. But although most take it to be a derogatory word for foreigner, call someone a gringo and what you’re really calling them is a Greek.

Pardon My French

People sometimes excuse themselves for cursing by saying “Pardon my French.” While it might be logical to assume that modern English curse words are somehow rooted in the French language, this is in fact, a myth. Instead, the origins of this phrase can be traced back to a centuries-long rivalry between the British and the French. As was the cultural norm back in 18th century England, anything dirty or sexual of nature was attributed to the French. Thus, according to Morris, kissing was called “French kissing,” syphilis was “French Pox” and uttering anything remotely vulgar, was labeled simply, “French.”

>> Try out these French curse words.

Seedy Motel

Think “seedy motel” and what may come to mind is the image of stained carpets, cigarette-scented pillowcases and a reception desk encased in bullet-proof glass. The last thing likely to come to mind is an eggplant but that is, in fact, where the word seedy stems from.

Apparently, vegetables “run to seed” if farmers wait too long to harvest them. Too full of seeds to be edible, the vegetables are thereby rendered useless and left to rot and decay, much like an old and dilapidated motel.

According to Morris, people first started to use the word seedy in a figurative sense in the 1730s, whereas the word motel, on the other hand, came into existence much later, in 1925. Motel is simply a combination of the words hotel and motor (short for motor car).

Wanderlust

Wanderlust is an example of what linguists refer to as a loanword: a word that’s been in a sense, loaned to one language from another, in this case, German. Lust is German for “desire” and wander comes from the German word wandern, which when translated literally, means “to hike.” Together, the two words form a compound adjective that describes that intense yearning travel-enthusiasts have to hit the open road and explore. Interestingly enough, while wanderlust now makes frequent appearances in English-language travel magazines and books around the world, it’s all but vanished from German vernacular entirely. It’s become outdated; replaced by the trendier fernweh. Fern is German for “far” and weh is German for “ache” and together, fernweh takes on the meaning of “farsick” (a derivative of heimweh, or homesick).

Wanderlust made its way into English because of the rise in popularity in travel at the turn of the last century. Perhaps as gap-years and overseas positions become more common, the need for an English word that captures the longing to live in a country other than one’s place of birth will arise and fernweh will, like wanderlust, wriggle its way into American vocabulary.

Need inspiration for your wanderlust? Read:

- Underrated US Cities and Why You Should Visit Them

- Around the World in Seven Lesser Known Islands

- The World’s Most Beautiful Coastal Towns

- Iceland’s Natural Wonders in Photos

- 10 Reasons to Visit Hawaii Now

- Affordable Places to Go on an African Safari

Photos by: NataPics, Maxime F, runran, Teppo, conorwithonen, benefit of hindsight, charchen, Ham Hock,