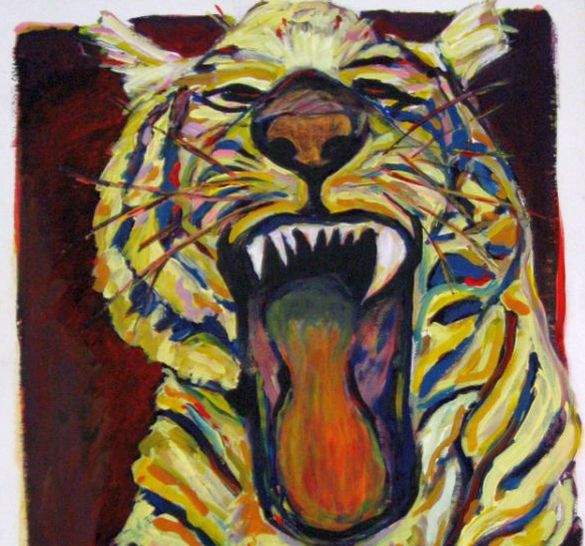

Oslo has a nickname among Norwegians – Tiger City – an innocent reminder that scratches are inevitable when in the capital city. My own reason for being here could give a scratch or two – to investigate the Norwegian folk soul, a concept which is supposed to express some common attitudes.

They are a small bunch, 4.7 million; that could be one reason why they appear close-knit, with many similarities in the way they act and think. My methods are very simple and unscientific – just strolling the streets with my eyes and ears as receivers. Not forgetting that a considerable portion of the population lives in more isolated spots with a life completely different from that in Oslo. In millions, the capital accounts for 0.6, its metropolitan area 1.4.

The national radio and TV have always helped neutralize the isolation, in particular with “Onskekoncerten”, a weekly music request program transmitting greetings and congratulations since 1950, in the golden age of radio with 75% of the listeners tuned in. It’s a radio classic, proving that the Norwegians always had their antennas out for international hits; in 1956 they were rocking around the clock with Bill Haley, two years later humming to a silvery moon with Billie Vaughn.

The geographical shape of Norway has given rise to thought experiments – if turning it around at its southernmost point, then Norway would suddenly reach Italy. That could be a practical position for a country nearly shaped as a pipeline, ready to open its oil taps and let the Norwegian gold flow to the South, in exchange for Italian opera for example, ready to fill an iceberg in the harbor of Oslo, or rather the new white opera building, Operaen.

The statue of a late diva, Kirsten Flagstad, turns its back on you, she looks out at Bjorvika, part of the Oslo Fjord, from where the Opera preferably should be approached. The large roads on the Opera’s back are waiting to be moved underground. A guided tour is most rewarding, at least with Berit, a retired member of the Opera Choir. The opera is a prestige project, the popularity of which appears gradually increasing from “Far too expensive!” to “We’ve got one too!”

Time for the mountains

Right behind the Opera lies Oslo S, the Central Railway Station. I expect half of Oslo to pass through here during the next few days, for it’s Easter now and everyone should be heading for the white mountains – armed with skis and rucksacks, colorful windbreakers over knickerbockers, spiced with home-knitted gloves and pixie caps with reindeers. But Oslo S is like any major train station: a mix of fastfood, cliques of young immigrants, guards and police on patrol, with eyes that could be a tiger’s.

We see skis that have been protectively wrapped up, by owners dressed in office gear. The nostalgic East Railway Station is still there, nowadays filled with various shops. The other half, the former West Station, over at the City Hall, has been turned into a high-tech Nobel Peace Center, very contemporary in that Barack Obama plays a dominating part, soon to be succeeded by a new Prize winner, Liu Xiaobo, Chinese writer and system critic.

The museum cannot be taken as a proof that Norwegians are more peace loving than other people, although the sheer focus on peace could rub off on people’s thinking, and Norwegian politicians occasionally seem to be involved in the negotiations of complicated international matters, pulling the strings rather than playing heroes. Their discreet contribution suits the Norwegians who are sometimes accused of being overly patriotic.

New countrymen

Preserving the peace seems to be important for every Norwegian, they are more than others expected to solve the problems of ill-adjusted second generation immigrants, whom they politely name “our new countrymen”. If you ask the locals about safety in a certain area, their politeness turns more practical: “I would not go there in the evening!” And if that is how their own neighborhood is: “I never go out after dark any more!”

One evening, in the street of Storgata, I drop into a pub called Dovrestua, with the restaurant Dovrehallen upstairs. It reminds me of my younger days when I used to have beers in a similar restaurant. The lady bartenders down in Dovrestua confirm that this is the very place – it’s like coming home! Another regular suddenly comes in quite agitated, his coat all wet. He keeps quiet awhile, then comes the outburst, “They threw a bottle at me! My new countrymen!” In the discussion that follows, diplomacy is laid aside, the tiger shows its claws.

Dovrestua is, however, also an example of peaceful co-existence, the owners are Asian immigrants, who loyally maintain Norwegian food traditions and employ locals to deal with the customers. The owners content themselves with the kitchen region. The same district has an unmistakable ethnic character – shops as well as eating places and people in the streets. Harassments are a bit innocent in my case – a young guy pops up at my side, like a tiger, and shouts right in my ear, obtaining exactly the shock effect he had in mind.

The neighborhood of Gronland is more hardcore ethnic, and most colorful, just east of Oslo S, among the locals called “Little Karachi”. Nearby is also the district of Grunerlokka, where the ethnic influence may be on the decline as the area grows trendy, with a multitude of cafes and restaurants in handsome old buildings, in a city where architecture can be a confusing mix.

No jump today

A bit confusing are also the national costumes paraded up the Karl Johan Street on May 17th, Constitution Day. They are so different, every locality has its own design and rules. These days, Norway’s national costumes are often made in China, still respecting local Norwegian traditions, thereby giving a national symbol an international touch, suggesting that Norwegian patriotism should be taken with a smile and a grain of salt.

If patriotism depends on status and welfare, then it should be more widespread on the western side of the river Akerselva, historically a division line with factories and working class districts on its eastern side. The revival of these districts makes it easier for the sun to come in, but the “sunny side of Akerselva” still refers to the west side. And the sun comes easily through in Oslo, during bitterly cold winters and hot summers. Climatic extremes coupled with Oslo’s natural surroundings are perhaps the main asset of the Norwegian capital.

Hills, forested and green or covered with snow, lakes for skating and swimming, and in the middle of it all, a brand new Holmenkollen Ski Jump. The T-train takes you there from Oslo S or upper Karl Johan. On a hill too small for present-day requirements, they built further into the air. Moving it was out of the question, for Holmenkollen is an inseparable part of the national heritage.

When a Norwegian jumper sets off into the air like a tiger, the law of gravity is abolished in all Norway, everyone goes with him, carried forward by the “Kollen roar” and relishing the panorama of Oslo and the Fjord. The new jump was opened by the first lady jumper ever, Anette Sagen from Mosjoen, the geographical center of Norway. In a few months, the whole world is invited to Holmenkollen, in the 2011 Nordic World Ski Championships, WSC, including cross-country and Nordic combined.

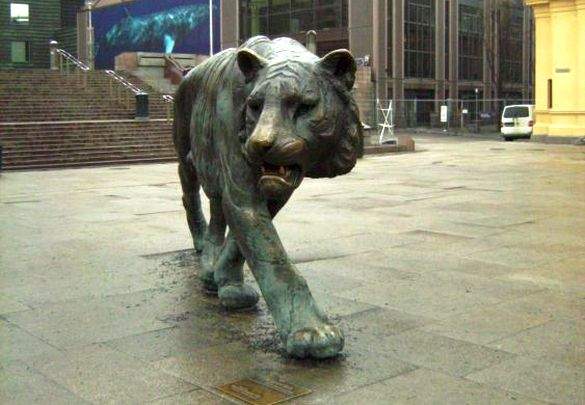

The Norwegian national anthem starts with “Yes, we love this country”, which seems to hold true still. Norwegian patriotism has many reasons – independence only since 1814, ample oil resources and world class ski athletes. This does not make them complacent though, for in every Norwegian hides a little peace negotiator. They even negotiated with the tiger of Oslo, now lurking idly around outside Oslo S, cast in bronze.

Painting by Lene Folkenberg, photos by Terje Raa