As a youngster growing up in Graz, Austria, my favorite part of the year was the month my parents and I spent at Altaussee, a picturesque village in the Alps and a popular resort. Of course, I showed it to my husband on our first trip to Europe, and I have since visited there with two of my sons. It was only on a recent visit that I learned that this seemingly remote spot in the Salzkammergut – as the area is known – played a role in World War II.

You don’t need to be a history buff to visit the two lakes or the salt mine where the events I’ll tell you about took place. They are beautiful and on the standard tourist itinerary. But if you like a bit of history in your travels, you may just choose to visit Altaussee and nearby Toplitzsee.

More than meets the eye

A German-language guide to local trails was my first clue, describing the capture of a high-ranking Nazi who had tried to hide out in the nearby mountains. Next was a popular three-lake boat trip. It ended not only with scrumptious pastries consumed at a lakeshore restaurant but also with buying postcards showing British pound notes said to have been hauled out of the lake.

On returning home I set out to learn more. I found that though these events are more than 60 years in the past they continue to generate lengthy discussions and exchanges on the Internet. Three years ago, the movie The Counterfeiters told the story of how that British currency was produced. The film received an Oscar for best foreign film of 2007, but it took some liberties. It was not in a cave that the currency was hidden at the end of the war. It was in a small lake.

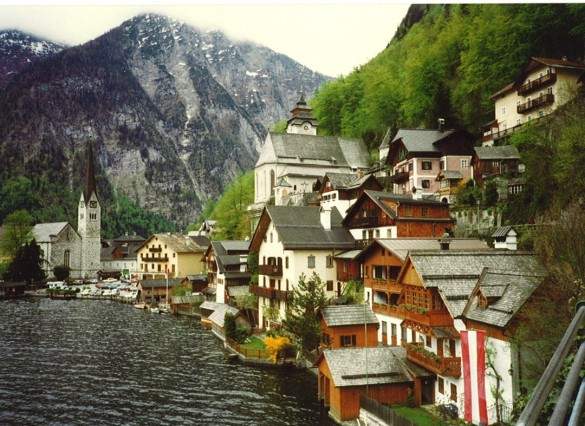

The Salzkammergut

Austria’s Salzkammergut east of Salzburg is a World Heritage site where the local industry – salt recovery – blends harmoniously into pristine alpine landscape. The name Salzkammergut refers to the area’s abundant salt deposits, intensively mined for over 900 years. Even in prehistoric times the Celtic Hallstatt culture, centered here, extracted and traded salt in the 7th century BC.

A lake full of surprises

Toplitzsee is the middle of a series of three lakes near Bad Aussee in a narrow valley surrounded by steep mountainsides. Tour boats take the traveler the length of each lake, providing views of spectacular scenery. The boat that cruises this particular lake passes two waterfalls to arrive at the destination restaurant, where a small exhibit tells the lake’s wartime story.

As you sip coffee at the Fischerhutte restaurant you are looking out over where the counterfeit money was dumped. In the waning days of Hitler’s Germany in spring 1945 desperate Nazi leaders hoped to hold out in a last redoubt in the Alps. Here their remaining forces would somehow survive to establish Hitler’s dreamed-of 1000-year Reich. But with defeat imminent, fake British currency, manufactured for an invasion that now clearly would not take place, needed to be discarded. The Counterfeiters told how the Nazis abruptly dismantled all printing equipment for disposal. Its depth made Toplitzsee seem the ideal depository for it and for crates full of pound notes. Who would ever find any of this in its 300-foot depth?

Someone did.

The German Navy had used the lake earlier in the war for testing underwater rockets and explosives. Rumors of gold in the lake began at war’s end, and many attempted to find it. The first to die while trying was a US Navy diver in 1947. In 1959, a German reporter found no gold but did bring what appeared to be 72 million pounds, in mint condition, to the surface. The saline content of the water near the bottom had perfectly preserved the counterfeiters’ product. A film the same year, The Treasure in Toplitzsee, speculated about its origin.

The lake was declared off limits after another death in 1963. In the 1980s authorized divers found more money, printing equipment, and other war materiel. Biologists returning frequently in recent years have discovered bacteria and a worm indigenous to the oxygen-free waters at depths below 60 feet. Dives for treasure routinely come up empty-handed because submerged logs block retrieval efforts, but speculation and attempts undoubtedly will continue.

Stolen art

And now back to the Nazi war criminal. In 2001 a Dutch tourist making a recreational dive at Altaussee lake came across a brass medal. It turned out to have belonged to Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the SS security chief, and one of the top Nazi leaders, including Adolf Eichmann, who had sought safety here. Kaltenbrunner apparently dropped it in the lake as he fled the approaching American army under another identity.

In the last days of the war, Kaltenbrunner had helped prevent the destruction of artworks stored in the local salt mine. These were not the holdings of German or Austrian museums, brought here to be safe from bombing raids. They were what Goering and other Nazi henchmen had stolen from individuals and museums in conquered countries for their own use or for Hitler’s planned Fuhrermuseum.

Adolf Hitler failed at art school, and the world knows the result of his turning to politics instead. Political success gave him another chance, and he began to collect art soon after attaining power. As German forces overran Austria, Poland, the Low Countries, and France, they emptied out the museums. The looting continued through the war years, with over one thousand cases arriving at Altaussee in 1944 and even early 1945, leaving little room for safe storage of legitimate museum treasures.

Allied troops neared the Salzkammergut in spring 1945. An eager local functionary took it upon himself to order bombs sent into the salt mine to destroy priceless art rather than have it fall into the hands of “Jews and Bolsheviks.” Neither management nor employees could countenance what would amount to destruction of the chief local industry that had employed generations of local families. Fortunately, it was known that Kaltenbrunner had a local girlfriend and was staying with her. He was contacted and agreed to order the removal of the bombs.

His self-interest is clear, as a few days later he looked for help to escape from the approaching Allies. For years an informal resistance group dedicated to Austrian independence had been in existence locally. Now they had a mission. Two local young men led the Kaltenbrunner party to a hunting lodge in the mountains. Upon return to the village, they alerted the occupation forces, already on the hunt for this most-wanted war criminal, and guided a US infantry detachment to the hideout. He was tried by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg and executed in October 1946.

Places to visit

The lodge is only accessible on foot, but anyone reasonably fit should have no trouble completing the six-mile hike from the end of the road up Loser mountain. A hut with overnight accommodations is nearby. The local Informationsburo (see Sidebar) can help with trail maps, possible guided hikes, and overnight arrangements.

The three-lake boat trip starts at Bad Aussee (see Sidebar), also known for its spa.

Guided tours of the Altaussee salt mine, approximately two miles from the village, take visitors through the underground chambers where the more than 6000 paintings, scuptures, graphic works, and tapestries, including the famous Eyck Ghent Altar, were stored. A multimedia presentation provides information about the hoarding and rescue of the art.

Salt mines at Hallstatt and Hallein also are open to visitors though without a share in the art story.