The entire city of Buenos Aires seems to drink mate. Families lounging on blankets pass it around in parks. Friends sitting on benches sip it while chatting. Beach-goers break out mate tote bags. Some devotees even juggle thermoses while biking or lug around special mate backpacks. My professors sipped it in class, and students gulped it while cramming at the university library. Argentines even use the verb matear, meaning “to share mate.”

The entire city of Buenos Aires seems to drink mate. Families lounging on blankets pass it around in parks. Friends sitting on benches sip it while chatting. Beach-goers break out mate tote bags. Some devotees even juggle thermoses while biking or lug around special mate backpacks. My professors sipped it in class, and students gulped it while cramming at the university library. Argentines even use the verb matear, meaning “to share mate.”

The cosmopolitan capital heavy with European influences brings to mind wistful Tango, elegant cafes and plastic surgery, but the ritual consumption of an ancient indigenous brew is perhaps its defining characteristic.

Mate (mah-tay), the beloved national drink of Argentina, transcends all borders. Dreadlocked, hemp-wearing types in plazas and suit-wearing, briefcase-toting types in offices both slurp the infusion. Packs of flirting teens with mullets and piercings take turns downing it, as do circles of chuckling grandparents with furs and pipes.

Some studies have reportedly found that 90 percent of Argentine households consume the beverage, making it profoundly more pervasive than any coffee or tea predilections stateside. Many fuel stations and restaurants offer customers hot water specifically to prepare their mate. The city’s many heladerias even deliver mate-flavored ice cream on motorbikes.

At first I feared joining in to sip the hot mixture, which drinkers pass around and share from a communal straw. It looked like murky lawn water, and I have germaphobe tendencies. But after trying the earthy liquid I wanted to pick up a package of Cruz de Malta and buy my own equipment. I asked my Argentine friends to teach me how to make it — They all demonstrated differing variations of the procedure.

I soon became obsessed with the mate ritual, preparing it myself for study sessions and serving it to houseguests. I imagined the refreshing drink contained an army of antioxidants and left me glowing. Many enthusiasts claim mate gives them the boost of coffee without the jitters. I found an overload of the caffeinated beverage to be my only means of surviving the all-night Buenos Aires weekend scene.

Mate, popular in various regions of South America, is made from dry yerba leaves resembling powdery grass that are steeped in hot water. It tastes like bitter tea, especially the green variety. People often add sugar. Some mothers even serve it to their children with milk or juice. Countless variations and brands of mate yerba (pronounced zsheer-buh by Argentines) tower the shelves of grocery stores, touting the drink’s supposed health, energy and weight loss benefits.

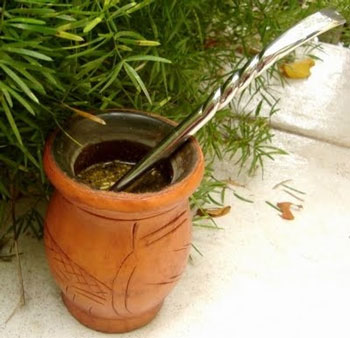

A special gourd container, also called a mate, holds the beverage. Many stores sell ornate mates, often embellished with silver. Every Argentine I met owned a well-used mate that they never washed in order to protect the flavor. In Iguazu, I bought a leather-covered mate made from a wood that only grows in the surrounding rainforest (or so said the owner of the shop off the red-orange dirt road). I cured my mate before using it like all my Argentine friends insisted. That involved scraping it, soaking it in yerba water for 24 hours and leaving it out to dry.

Mate drinkers sip through a straw called a bombilla (bom-bee-zshuh), usually silver or the cheaper Alpaca. The small holes and sieve in the bulbous end of the bombilla filter the yerba from the water. First-time drinkers must resist the urge to stir the bombilla and instead let the mixture float to prevent particles from clogging the straw.

Mate is more than a social pastime – some Argentines consider mate preparation and service an art with all sorts of rules. Making mate involves a controversial process involving shaking, piling, and arranging the yerba before pouring in cold then hot water and packing and tapping. The water must never be boiling, or it will scald the yerba. The person serving the mate, the cebador, must drink the first cup, which is the most bitter. After washing it down, the cebador then refills the mate cup with fresh hot water and passes it to the next recipient, who also drains the cup until the straw makes a slurping sound (this isn’t rude). Everyone continues taking turns, handing the mate back with the straw facing the cebador for the next person’s refill until the mate is lavado, meaning it’s lost its flavor. All the sharing lends an intimate element to the proceedings.

I constantly served mate with my Peruvian roommates. We heated water in a kettle on our gas stove and sat it on a coaster in the floor of our unfurnished apartment in Barrio Norte. We’d sprawl out and pass around the mate while we shared travel photos, munched galletas, listened to cumbia or watched translated episodes of Sex and the City. When it came time for me to return to the U.S. after my seven months in Argentina, I ended up hailing a taxi to the airport in a manic rush, dragging my two overstuffed suitcases. I bemoaned to the characteristically friendly taxista that I’d been kicked out of my apartment early and hadn’t finished my souvenir shopping. We chatted about my trip to Iguazu Falls, and he pulled out a photo of his family. When we drove up to the departures gate, he helped me unload my bags from the trunk. “Wait,” he said, rifling through the glove compartment to dig out a worn mate. “Take it. Remember Buenos Aires. It’s my gift.”